Monday, April 10, 2023

The Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905 was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire, some of which was directed at the government. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies. It led to constitutional reform (namely the "October Manifesto"), including the establishment of the State Duma, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906.

Aided by Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese war (1904–1905), the Russian revolution of 1905 was the collective backlash of the masses against the corrupt, incompetent, and uncaring autocracy of the Tsarist Regime which was unable and unwilling to change with the times.

The indirect causes of the 1905 Revolution laid in the social, political, agrarian, and industrial developments that marked the preceding century. Since 1861, emancipated serfs had become “free” peasants, though they were still tied to the communal agricultural system. Their earnings were often so small that they could neither buy the food they needed nor keep up the payment of taxes and redemption dues they owed the government for their land allotments. There was general agreement at the turn of the century that Russia faced an acute and intensifying agrarian crisis due mainly to rural overpopulation.

Another cause of the revolution was the radicalization of the educated class. During 1860s were lifted many restrictions on universities, and mandatory uniforms and military discipline were abolished. This resulted in a new freedom in the content and reading lists of academic courses. As universities expanded, there was a rapid growth of newspapers, journals, and an organization of public lectures

and professional societies. This created the idea of their right to have an independent opinion.

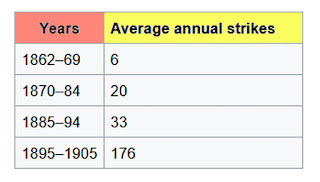

The conditions at the Russia factories were unbearably miserable and the workers were often unhappy with their deplorable work environment. Russian industrial workers were also the lowest-wage workers in Europe. Since many had come to the cities to work in these factories, they had become increasingly literate and aware of their situation. As a result, worker strikes and general discontent were commonplace. These discontented, radicalized workers became key to the revolution by participating in illegal strikes and revolutionary protests.

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putilov plant (a railway and artillery supplier) in St. Petersburg. Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers to 150,000 workers in 382 factories. By 21 January 1905, the city had no electricity and newspaper distribution was halted. All public areas were declared closed.

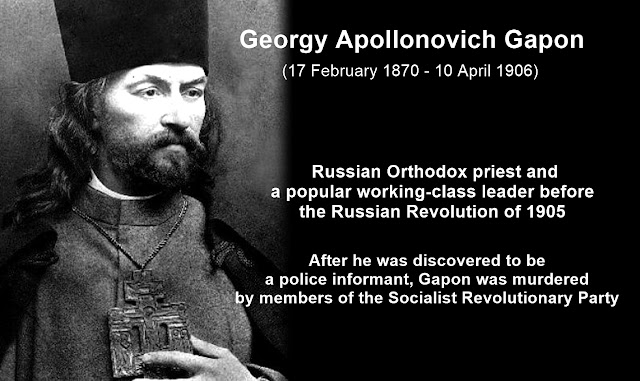

Controversial Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon, led a huge workers' procession to the Winter Palace to deliver a petition to the Tsar on Sunday, 22 January 1905. Protesters were simply asking for moderate change from the Tsar. The demonstrators held up images and symbols of the Tsar and Tsarina, indicating their support for their leaders. The troops guarding the Palace opened fire on the demonstrators, causing a few hundred deaths. The event became known as Bloody Sunday, and is considered by many scholars as the start of the active phase of the revolution.

The news of the massacre spread around the country, prompting further strikes in other areas of the empire. Half of European Russia's industrial workers went on strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland. There were also strikes in Finland and the Baltic coast. In Riga, 130 protesters were killed on 26 January, and in Warsaw a few days later over 100 strikers were shot on the streets. By February, there were strikes in the Caucasus, and by April, in the Urals and beyond. In June and July 1905, there were many peasant uprisings in which peasants seized land and tools.

In March, all higher academic institutions were forcibly closed for the remainder of the year, adding radical students to the striking workers. A strike by railway workers on 21 October 1905 quickly developed into a general strike in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. By 26 October 1905, over 2 million workers were on strike and there were almost no active railways in all of Russia. Growing inter-ethnic confrontation throughout the Caucasus resulted in Armenian-Tatar massacres, heavily damaging the cities and the Baku oilfields.

There were naval mutinies at Sevastopol, Vladivostok, and Kronstadt, peaking in June with the mutiny aboard the battleship Potemkin. The mutineers eventually surrendered the battleship to Romanian authorities on 8 July in exchange for asylum, then the Romanians returned her to Imperial Russian authorities on the following day. Some sources claim over 2,000 sailors died in the suppression.

The Trans-Baikal railroad fell into the hands of striker committees and demobilised soldiers returning from Manchuria after the Russo–Japanese War. The Tsar had to send a special detachment of loyal troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway to restore order. Despite these mutinies, the armed forces were largely apolitical and remained mostly loyal, and were widely used by the government to control the 1905 unrest.

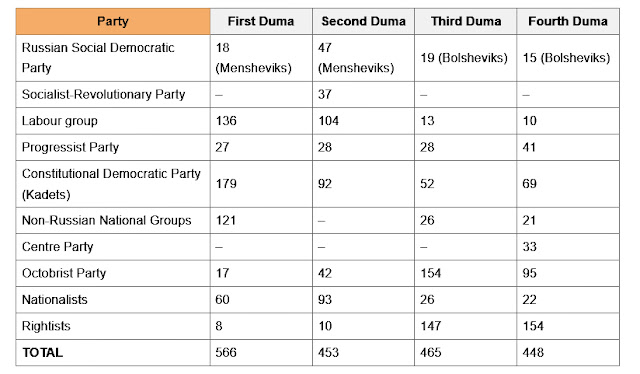

Nicholas responded in February by announcing his intention to establish a State Duma of the Russian Empire but with consultative powers only. His proposal did not satisfy the striking workers, the peasants, or even the liberals.

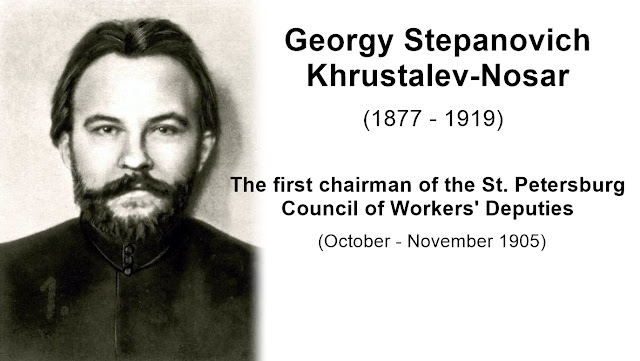

The government decree on August 6 announcing election procedures for the advisory assembly stimulated even more protest, which increased through September. The rebellion reached its peak in October-November. A railroad strike, begun on October 7, swiftly developed into a general strike in most of the large cities. The first workers’ council, or soviet, acting as a strike committee, was formed at Ivanovo-Vosnesensk; another, the St. Petersburg soviet, was formed on October 13. It initially directed the general strike; but, as social democrats, especially Mensheviks, joined, it assumed the character of a revolutionary government. Similar soviets were organized in Moscow, Odessa, and other cities.

The magnitude of the strike finally convinced Nicholas to act. He signed the October Manifesto on October 30, 1905, which promised a constitution and the establishment of an elected legislature. These concessions were considered enough by moderate revolutionaries who were satisfied, and many workers, interpreting the October Manifesto as a victory, returned to their jobs. This was enough to break the opposition’s coalition and to weaken the St. Petersburg soviet.

While the Russian liberals were satisfied by the October Manifesto and prepared for upcoming Duma elections, radical socialists and revolutionaries denounced the elections and called for an armed uprising to destroy the Empire.

At the end of November the government arrested the soviet’s chairman, the Menshevik Georgy Stepanovich Khrustalev-Nosar, and in December occupied its building and arrested Leon Trotsky and others.

Between 5 and 7 December, there was a general strike by Russian workers in Moscow. The government sent troops on 7 December, and a bitter street-by-street fight began. A week later, the Semyonovsky Regiment was deployed, and used artillery to break up demonstrations and to shell workers' districts. On 18 December, with around a thousand people dead and parts of the city in ruins, the workers surrendered.

Special military expeditions were sent to Poland, the Baltic provinces, and Georgia, where the suppression of the rebellions was particularly bloody. By the beginning of 1906 the government had regained control of the Trans-Siberian Railroad and of the army, and the revolution was essentially over.

The uprising failed to replace the tsarist autocracy with a democratic republic or even to convoke a constituent assembly, and most of the revolutionary leaders were placed under arrest. At least 1500 czarist soldiers or bureaucrats died in the revolution. About 15,000 rebels and noncombatants were killed and 20,000 wounded, with 38,000 imprisoned.

The Russian Constitution of 1906, also known as the Fundamental Laws, set up a multiparty system and a limited constitutional monarchy. The revolutionaries were quelled and satisfied with the reforms, but it was not enough to prevent the 1917 revolution that would later topple the Tsar's regime.