Sunday, April 9, 2023

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état was a watershed event in both the history of Chile and the Cold War. Following an extended period of social unrest and political tension between the right-controlled Congress of Chile and the socialist President Salvador Allende, as well as economic warfare ordered by U.S. President Richard

Nixon, Allende was overthrown by the armed forces and national police. Before the coup, Chile had for decades been hailed as a beacon of democracy and political stability while the rest of South America had been plagued by military juntas and Caudillismo. The collapse of Chilean democracy ended a streak of democratic governments in Chile, which had held democratic elections since 1932.

In 1970 Salvador Allende won the presidency in a close three-way race. He was elected in a run-off by Congress as no candidate had

gained a majority. As president, Allende adopted a policy of nationalization of industries and collectivization. Due to these and other factors, increasingly strained relations between him and the legislative and judicial branches of the Chilean government culminated in a declaration by Congress of a "constitutional breakdown". A centre-right majority including the Christian Democrats, whose support had enabled Allende's election, denounced his rule as unconstitutional and called for his overthrow by force. On 11 September 1973, the military moved to oust Allende in a coup d'état supported by the United States Central Intelligence Agency.

By 7:00 am, the Navy captured Valparaíso, strategically stationing ships and marine infantry in the central coast and closed radio and television networks. The Province Prefect informed President Allende of the Navy's actions; immediately, the president went to the presidential palace with his bodyguards, the "Group of Personal Friends". By 8:00 am, the Army had closed most radio and television stations in Santiago city. The Air Force bombed the remaining active stations, but the President received incomplete information, and was convinced that only a sector of the Navy conspired against him and his government.

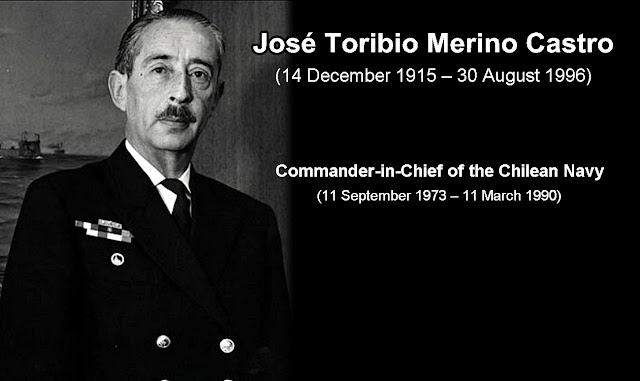

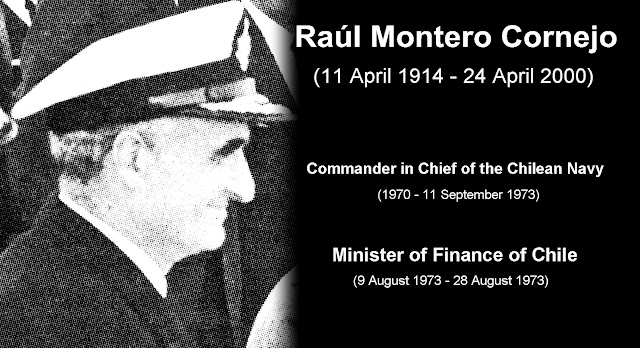

President Allende and Defence minister Orlando Letelier were unable to communicate with military leaders. Admiral Montero, the Navy's commander and an Allende loyalist, was rendered incommunicado. His telephone service was cut and his cars were

sabotaged before the coup d’état, to ensure he could not thwart the opposition. Leadership of the Navy was transferred to José Toribio Merino, planner of the coup d’état and executive officer to Admiral

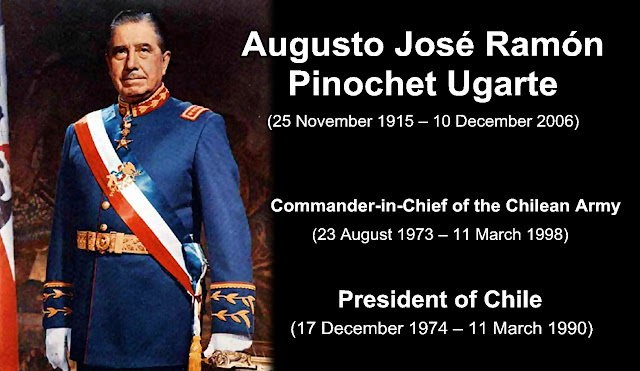

Montero. Augusto Pinochet, General of the Army, and Gustavo Leigh, General of the Air Force, did not answer Allende's telephone calls to them. The General Director of the Carabineros, José María

Sepúlveda, answered Allende's call and immediately went to the La Moneda presidential palace. When Defence minister Letelier arrived at the Ministry of Defense, controlled by Admiral Patricio Carvajal, he was arrested as the first prisoner of the coup d’état.

Despite evidence that all branches of the Chilean armed forces were involved in the coup, Allende hoped that some units remained loyal to the government. Allende was convinced of Pinochet's loyalty, telling a reporter that the coup d’état leaders must have imprisoned the general. Only at 8:30 am, when the armed forces declared their control of Chile and that Allende was deposed, did the president grasp the magnitude of the military's rebellion. Despite the lack of any military support, Allende refused to resign his office.

At approx. 9:00 the carabineros of the La Moneda left the building. By 9:00 am, the armed forces controlled Chile, except for the city centre of the capital, Santiago. Allende refused to surrender, despite the military's declaring they would bomb the La Moneda presidential palace if he resisted being deposed. The Socialist Party proposed to Allende that he escape to the San Joaquín industrial zone in southern Santiago, to later re-group and lead a counter-coup d’état; the president rejected the proposition. The military attempted negotiations with Allende, but the President refused to resign, citing his constitutional duty to remain in office. Finally, Allende gave a farewell speech, telling the nation of the coup d’état and his refusal to resign his elected office under threat.

Leigh ordered the presidential palace bombed, but was told the Air Force's Hawker Hunter jet aircraft would take forty minutes to arrive. Pinochet ordered an armoured and infantry force under General Sergio Arellano to advance upon the La Moneda presidential palace. When the troops moved forward, they were forced to retreat after coming under fire from Allende’s snipers

perched on rooftops. General Arellano called for helicopter gunship support from the commander of the Chilean Army Puma helicopter squadron and the troops were able to advance again. Chilean Air Force aircraft soon arrived to provide close air support for the assault, by bombing the Palace, but the defenders did not surrender until nearly 2:30 pm. First reports said the 65-year-old president had died fighting troops, but later police sources reported he had committed suicide.

Sixty individuals died as a direct result of fighting on 11 September, although the fight continued the following day. In all, 46 of Allende's guard were killed, some of them in combat with the soldiers that took the Moneda. On the military side, there were 34 deaths. In mid-September, the Chilean military junta claimed its troops suffered another 16 dead and 100 injured by gunfire in mopping-up operations against Allende supporters.

On 13 September, the Junta dissolved Congress. At the same time, it outlawed the parties that had been part of the Popular Unity coalition, and all political activity was declared "in recess".

In the first months after the coup d’état, the military killed thousands of Chilean leftists, both real and suspected, or forced their "disappearance". The military imprisoned 40,000 political enemies in the National Stadium of Chile. The government arrested some 130,000 people in a three-year period.

Allende's appointed army chief, Augusto Pinochet, rose to supreme power within a year of the coup, formally assuming power in late 1974. The United States government, which had worked to create the conditions for the coup, promptly recognized the junta government and supported it in consolidating power.