Friday, April 7, 2023

The American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), also referred to as the American War of Independence and as the Revolutionary War in the United States, was an armed conflict between Great Britain and those thirteen of its North American colonies which after the onset of the war declared independence as the United States of America.

The close of the Seven Years' War in 1763 saw Great Britain triumphant in driving the Kingdom of France from North America, but heavily in debt. Britain's national

debt at the end of the war had doubled to £130,000,000 and the annual cost of the British civil and military establishment in America in 1764 was £350,000, five times the cost of 15 years earlier. Parliament passed the Stamp Act in March 1765, which imposed direct taxes on the colonies for the first time. This was met with strong condemnation among American spokesmen, who argued that their "Rights as Englishmen" meant that there could be "no taxation without representation"—that is direct taxes could not be imposed on them by Parliament because they lacked representation in Parliament.

This resistance became particularly widespread in the New England

Colonies, especially in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Patriot protests escalated into boycotts. On December 16, 1773, Massachusetts members of the Patriot group Sons of Liberty destroyed a shipment of tea in Boston Harbor in an event that became known as the Boston Tea Party. The British government retaliated by closing the port of Boston and enacting punitive measures against Massachusetts, including the dissolution of its charter and the prohibition of its

traditional, democratic town meetings. Named the "Coercive Acts" by Parliament, these measures became known as the Intolerable Acts in America. The Massachusetts colonists responded with the Suffolk Resolves, establishing a shadow government that removed control of the province from the Crown outside of Boston. Twelve colonies formed a Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance, and established committees and conventions that effectively seized power.

British attempts to seize the munitions of Massachusetts colonists in April 1775 led to the first open combat between Crown forces and Massachusetts militia, the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. Militia forces proceeded to besiege the British forces in Boston, forcing them to evacuate the city in March 1776. The Continental Congress appointed George Washington to take command of the militia. Later he was appointed as commander-in-chief of the newly formed Continental Army, as well as coordinating state militia units. Concurrent to the Boston campaign, an American attempt to invade Quebec and raise rebellion against the British Crown there decisively failed. On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress formally voted for independence, issuing its Declaration on July 4.

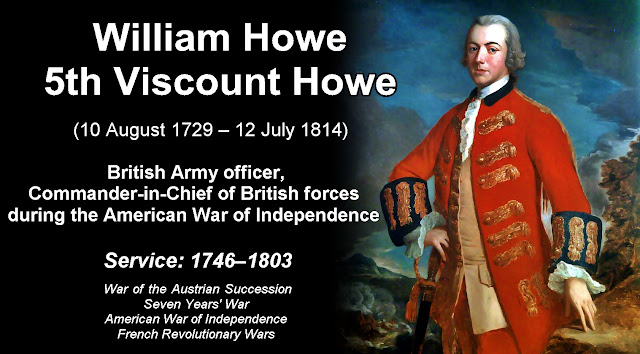

Sir William Howe began a British counterattack, focussing on recapturing New York City. Howe outmaneuvered and defeated Washington, leaving American confidence at a low ebb. Washington captured a Hessian force at Trenton and drove the British out of New Jersey, restoring American confidence. In 1777 the British sent a new army under John Burgoyne to move south from Canada and to isolate the New England colonies. However, instead of assisting Burgoyne, Howe took his army on a separate campaign against the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia. Burgoyne outran his supplies, was surrounded and surrendered at Saratoga in October 1777.

The British defeat in the Saratoga Campaign had drastic consequences. France and Spain had covertly provided the colonists with weapons, ammunition, and other supplies since April 1776; in 1778 France formally entered the war, signing a military alliance that recognized the independence of the United States. Giving up on the North, the British decided to salvage their former colonies in the South. British forces under Lieutenant- General Charles Cornwallis seized Georgia and South Carolina, capturing an American army at Charleston, South Carolina in May 1780. British strategy depended upon an uprising of large numbers of armed Loyalists, but too few came forward. In 1779 Spain joined the war as an ally of France under the Pacte de Famille, intending to capture Gibraltar and British colonies in the Caribbean. Britain declared war on the Dutch Republic in December 1780.

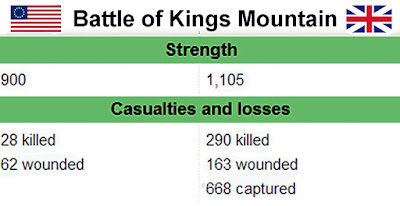

In 1781, after the British and their allies had suffered two decisive defeats at King's Mountain in October 1780 and Cowpens in January 1781, Cornwallis retreated to Virginia, intending on evacuation. A decisive French naval victory in September deprived the British of an escape route. A joint Franco-American army led by Count Rochambeau and Washington, laid siege to the British forces at Yorktown. With no sign of relief and the situation untenable, Cornwallis surrendered in October 1781, and some 8,000 soldiers were taken prisoner.

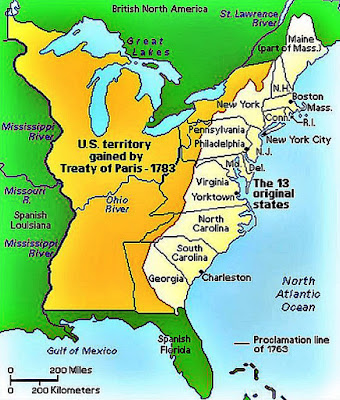

Whigs in Britain had long opposed the pro-war Tory majority in Parliament, but the defeat at Yorktown gave the Whigs the upper hand. In early 1782 they voted to end all offensive operations in North America, but the British war against France and Spain continued, with the British decisively defeating both during the Great Siege of Gibraltar. In addition Britain inflicted several naval defeats upon the French, most decisively in the Battle of the Saintes in the Caribbean in April 1782. On September 3, 1783, the combatants signed the Treaty of Paris, ending the war. Britain agreed to recognize the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded roughly by present-day Canada to the north, by Florida to the south, and by the Mississippi River to the west.

While French involvement proved decisive for the cause of American independence, France made only minor territorial gains, and incurred massive financial debts. Spain acquired Britain's Florida colonies and the island of Minorca, but failed in its primary aim of recovering Gibraltar. The Dutch lost on all counts, and had to cede Nagapattinam to the British.

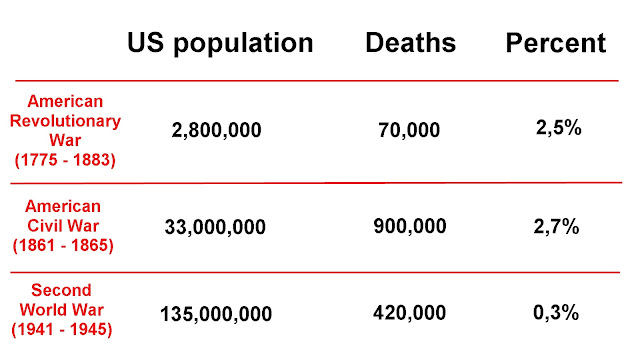

The total loss of life throughout the war is largely unknown. As was typical in the wars of the era, disease claimed far more lives than battle. At least 25,000 American Patriots died during active military service. Proportionate to the population of the colonies, the Revolutionary War was at least the second-deadliest conflict in American history, ranking ahead of World War II and behind only the Civil War.