Sunday, April 9, 2023

The Battle of Kadesh

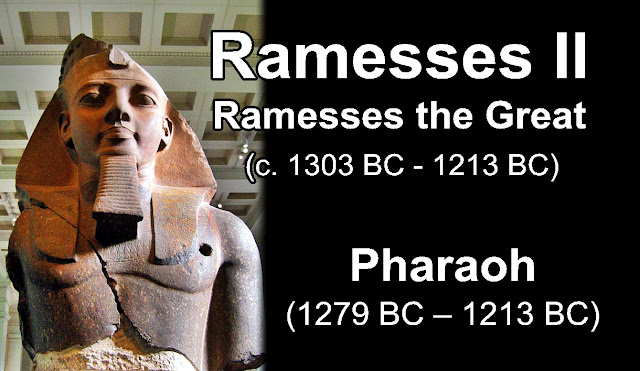

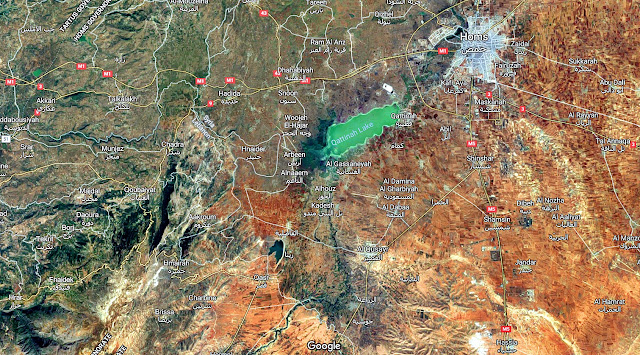

The Battle of Kadesh took place between the forces of the Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River, just upstream of Lake Homs near the modern Syrian-Lebanese border.

The battle is generally dated to 1274 BC in the conventional Egyptian chronology, and is the earliest battle in recorded history

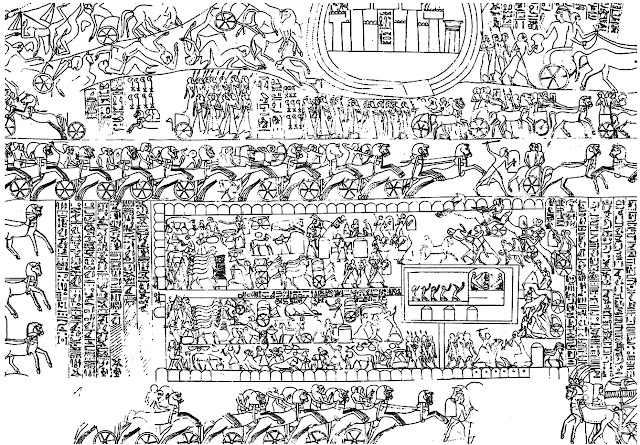

for which details of tactics and formations are known. It is believed to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving between 5,000 and 6,000 chariots in total. As a result of the multiple Kadesh inscriptions, it is the best documented battle in all of ancient history.

After expelling the Hyksos 15th dynasty around 1550 BC, the native Egyptian New Kingdom rulers became more aggressive in

reclaiming control of their state's borders. Many of the Egyptian campaign accounts between 1400 and 1300 BC reflect the general destabilization of the region of the Djahi, or Southern Canaan, and Egypt continued to lose territory to Mitanni Kingdom in northern Syria. Horemheb, the last ruler of the 18th dynasty, campaigned in this region, finally beginning to turn Egyptian interest back to this region.

This process continued in the 19th Dynasty, when Seti I took 20,000 men and reoccupied abandoned Egyptian posts and garrisoned cities. He made an informal peace with the Hittites, took

control of coastal areas along the Mediterranean, and continued to campaign in Canaan. A second campaign led to his capture of Kadesh and the Kingdom of Amurru. However, at some point both regions may have lapsed back into Hittite control.

The immediate antecedents to the Battle of Kadesh were the early campaigns of Ramesses II into Canaan. In the fourth year of his reign, he marched north into Syria, either to recapture Amurru, or, as a probing effort, to confirm his vassals' loyalty and explore the terrain of possible battles. The recovery of Amurru was Muwatalli's stated motivation for marching south to confront the Egyptians.

Ramesses' army crossed the Egyptian border in the spring of year five of his reign and, after a month's march, reached the area of Kadesh from the south. Ramesses led an army of four divisions: Amun, Re, Seth and the apparently newly formed Ptah division.

The Hittite king Muwatalli, had positioned his troops behind "Old Kadesh", but Ramesses, misled by two spies whom the Egyptians

had captured, thought the Hittite forces were still far off, at Aleppo, and ordered his forces to set up camp. As Ramesses and the Egyptian advance guard were about 11 kilometers from Kadesh, south of Shabtuna, he met two Shasu nomads who told him that the Hittite king was "in the land of Aleppo, 200 kilometers away. An Egyptian scout then arrived at the camp bringing two Hittite prisoners. The prisoners revealed that the entire Hittite army and the Hittite king were actually close at hand.

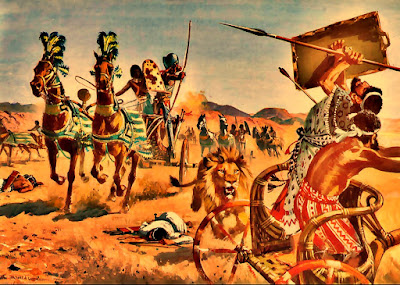

As Ramesses was alone with his bodyguard and the Amun division, the vizier was ordered to hasten the arrival of the Ptah and Seth divisions, with the Re division having almost arrived at the camp. While Ramesses was talking with the princes, the Hittite chariots

crossed the river and charged the middle of the Re division as they were making their way toward Ramesses' position. The Re division was caught in the open and scattered in all directions. Some fled northward to the Amun camp, all the while being pursued by Hittite chariots.

The Hittite chariotry then rounded north and attacked the Egyptian camp, crashing through the Amun shield wall and creating panic among the Amun division. However, the momentum of the Hittite

attack was already starting to wane, as the impending obstacles of such a large camp forced many Hittite charioteers to slow their attack, and some were killed in chariot crashes.

The Hittites, who believed their enemies to be totally routed, had stopped to plunder the Egyptian camp and, in doing so, became easy targets for Ramesses' counterattack. Ramesses' action was successful in driving the looters back towards the Orontes river and away from the Egyptian camp, while in the ensuing pursuit, the heavier Hittite chariots were easily overtaken and dispatched by the lighter, faster, Egyptian chariots.

Although he had suffered a significant reversal, Muwatalli still commanded a large force of reserve chariotry and infantry, plus the walls of the town. As the retreat reached the river, he ordered another thousand chariots to attack the Egyptians, the stiffening element consisting of the high nobles who surrounded the king. As the Hittite forces approached the Egyptian camp again, the Ptah division arrived from the south, threatening the Hittite rear.

After six charges, the Hittite forces were almost surrounded, and the survivors were pinned against the Orontes. The remaining Hittite elements not overtaken in the withdrawal were forced to abandon their chariots and attempt to swim across the river, where many of them drowned. The Hittite army was ultimately forced to retreat, but the Egyptians were unsuccessful in capturing Kadesh.

Logistically unable to support a long siege of the walled city of Kadesh, Ramesses gathered his troops and retreated south towards Damascus and ultimately back to Egypt. Once back in Egypt, Ramesses proclaimed victory, having routed his enemies, however he didn't try further to capture Kadesh. In a personal sense, however, the Battle of Kadesh was a triumph for Ramesses since, after blundering into a devastating Hittite chariot ambush, the young king had courageously rallied his scattered troops to fight on

the battlefield while escaping death or capture. The new lighter, faster, two-man Egyptian chariots were able to pursue and take down the slower three-man Hittite chariots from behind as they overtook them.

Hittite records from Boghazkoy, however, tell of a very different conclusion to the greater campaign, where a chastened Ramesses was forced to depart from Kadesh in defeat. Modern historians essentially conclude the battle was a draw, a great moral victory for the Egyptians, who had developed new technologies and rearmed before pushing back against the years-long steady incursions by the Hittites.

The running borderlands conflicts between the Egyptian Empire and the Hittite Empire were finally concluded some fifteen years after the Battle of Kadesh by an official peace treaty in the 21st year of Ramesses ii reign, 1258 BC in conventional chronology, with Hattusili III, the new king of the Hittites. The treaty that was

established was inscribed on a silver tablet, of which a clay copy survived in the Hittite capital of Hattusa, in modern Turkey, and is on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. An enlarged replica of the Kadesh agreement hangs on a wall at the headquarters of the United Nations, as the earliest international peace treaty known to historians.