Sunday, April 9, 2023

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in august 1968

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, officially known as Operation Danube, was a joint invasion of Czechoslovakia by five Warsaw Pact nations – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Hungary, East Germany and Poland – on the night of 20–21 August 1968. The invasion successfully stopped Alexander Dubček's Prague Spring liberalisation reforms and strengthened the authority of the authoritarian wing within the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

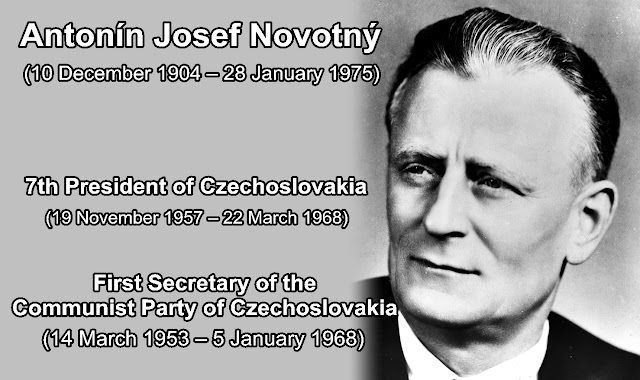

The process of de-Stalinization in Czechoslovakia had begun under Antonín Novotný in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but had progressed more slowly than in most other states of the Eastern Bloc. In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia underwent an economic

downturn. The Soviet model of industrialization applied poorly to Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was already quite industrialized before World War II and the Soviet model mainly took into account less developed economies. Novotný's attempt at restructuring the economy, the 1965 New Economic Model, spurred increased demand for political reform as well.

Novotný invited the secretary-general of the Communist Party of Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev, to Prague in December 1967, seeking support, but Brezhnev was surprised at the extent of the opposition to Novotný and thus supported his removal as Czechoslovakia's leader. Dubček replaced Novotný as First Secretary on 5 January 1968. On 22 March 1968, Novotný resigned his presidency and was replaced by Ludvík Svoboda, who later gave consent to the reforms.

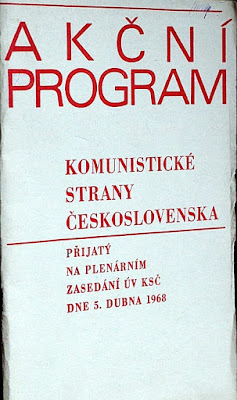

In April, Dubček launched an "Action Programme" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement, with economic emphasis on consumer goods and the possibility of a multiparty

government. It would limit the power of the secret police and provide for the federalization of Czechoslovakia into two equal nations. The programme also covered foreign policy, including both the maintenance of good relations with Western countries and cooperation with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc nations. It spoke of a ten-year transition through which democratic elections would be made possible and a new form of democratic socialism would replace the status quo.

Although it was stipulated that reform must proceed under Communist Party direction, popular pressure mounted to implement reforms immediately. Radical elements became more vocal. Anti-Soviet polemics appeared in the press, after the formal abolishment of censorship on 26 June 1968, the Social Democrats began to form a separate party, and new

unaffiliated political clubs were created. Party conservatives urged repressive measures, but Dubček counselled moderation and re-emphasized the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia leadership. At the Presidium of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in April, Dubček announced a political programme of "socialism with a human face". In May, he announced that the Fourteenth Party Congress would convene in an early session on 9 September. The congress would incorporate the Action Programme into the party statutes, draft a federalization law, and elect a new Central Committee.

The Soviet leadership at first tried to stop or limit the impact of Dubček's initiatives through a series of negotiations. Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union agreed to bilateral talks to be held in July 1968 at Čierna nad Tisou, near the Slovak-Soviet border. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia delegates reaffirmed their loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and promised to curb "anti-socialist" tendencies, prevent the revival of the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Party, and control the press by the re-imposition of a higher level of censorship. In return the USSR agreed to withdraw their troops, still stationed in Czechoslovakia since the June 1968 maneuvers, and permit 9 September party congress.

As these talks proved unsatisfactory, the USSR began to consider a military alternative. The Soviet Union's policy of compelling the socialist governments of its satellite states to subordinate their national interests to those of the Eastern Bloc, through military force if needed, became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine.

At approximately 11 pm on 20 August 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia. That night, 250,000 Warsaw Pact troops and 2,000 tanks entered the country. Total number of invading troops eventually reached 500,000. Romania did not take part in the invasion, nor did Albania, which subsequently withdrew from the Warsaw Pact over the matter. Participation of the German Democratic Republic was cancelled just hours before the invasion.

The decision for the non-participation of the East German Army in the invasion was indeed made on short notice by Brezhnev following requests by high-ranking Czechoslovak opponents of Dubcek who feared of much larger Czechoslovak resistance if German troops were present on Czechoslovak territory due to previous Czech experience with German occupation of Czechoslovakia.

The invasion was well planned and coordinated; simultaneously with the border crossing by ground forces, a Soviet airborne division captured Prague Václav Havel Airport, at the time called Ruzyne International Airport, in the early hours of the invasion. It began with a special flight from Moscow which carried more than 100 plain clothes agents. They quickly secured the airport and prepared the way for the huge forthcoming airlift, in which An-12 transport aircraft began arriving and unloading Soviet airborne troops equipped with artillery and light tanks. As the operation at the airport continued, columns of tanks and motorized rifle troops headed toward Prague and other major centers, meeting no resistance.

During the attack of the Warsaw Pact armies, 137 Czechs and Slovaks were killed, 19 of those in Slovakia, and hundreds were wounded. Alexander Dubček called upon his people not to resist. He was arrested and taken to Moscow along with several of his colleagues. Dubček and most of the reformers were returned to Prague on 27 August, and Dubček retained his post as the party's first secretary until he was forced to resign in April 1969 following the Czechoslovak Hockey Riots.

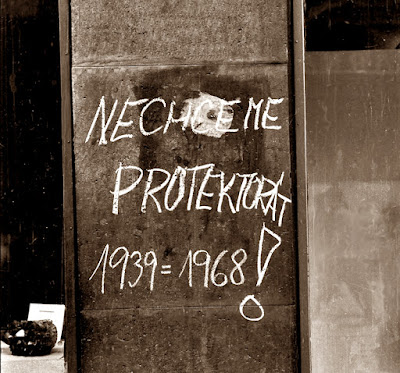

Popular opposition was expressed in numerous spontaneous acts of nonviolent resistance. In Prague and other cities throughout the republic, Czechs and Slovaks greeted Warsaw Pact soldiers with arguments and reproaches. Every form of assistance, including the provision of food and water, was denied to the invaders. Signs, placards, and graffiti drawn on walls and pavements denounced the invaders, the Soviet leaders, and suspected collaborationists. Pictures of Dubček and Svoboda appeared in the streets. Citizens gave wrong directions to soldiers and even removed street signs, except for those giving the direction back to Moscow.

The generalised resistance caused the Soviet Union to abandon its original plan to oust the First Secretary. It was agreed that Dubček would remain in office, but he was no longer free to pursue liberalisation as he had before the invasion. The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, largely of highly qualified people, unseen before and stopped shortly after, 70,000 immediately and 300,000 in total. Western countries allowed these people to immigrate without complications.

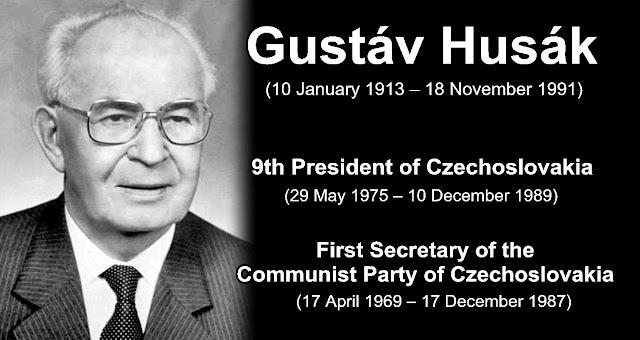

Finally, on 17 April 1969, Dubček was replaced as First Secretary by Gustáv Husák, and a period of "Normalization" began. Pressure from the Soviet Union pushed politicians to either switch loyalties or simply give up. In fact, the very group that voted in Dubček and

put the reforms in place were mostly the same people who annulled the program and replaced Dubček with Husák. Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of its liberal members, and dismissed the professional and intellectual elites who openly expressed disagreement with the political turnaround from public offices and jobs. By May 1971, Husák could report to the delegates attending the officially sanctioned Fourteenth Party Congress that the process of normalization had been completed satisfactorily and that Czechoslovakia was ready to proceed toward higher forms of socialism.