Sunday, April 9, 2023

The Finnish - Soviet war

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland, It began with a Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939, three months after the outbreak of the second World War, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940.

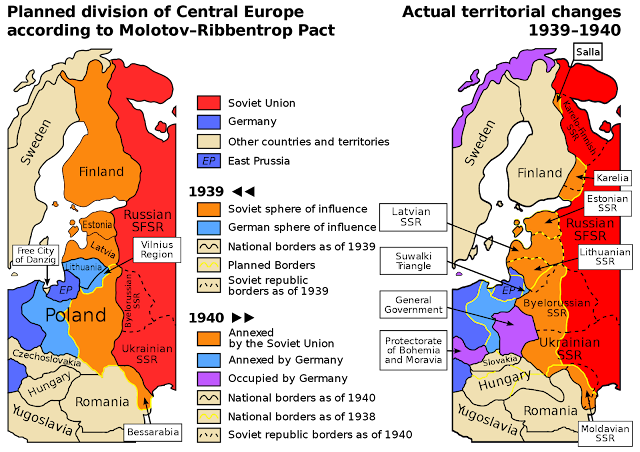

The Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939. The pact was nominally a non-aggression treaty, but it included a secret protocol in which Eastern European countries were divided into spheres of interest. Finland fell into the Soviet sphere.

On 5 October 1939, the Soviet Union invited a Finnish delegation to Moscow for negotiations. The Soviet delegation demanded that the border between the USSR and Finland on the Karelian Isthmus be moved more westward to a point only 30 kilometers east of Vyborg and that Finland destroy all existing fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus. The Soviets were claiming security reasons, primarily the protection of Leningrad, 32 kilometers from the

Finnish border. Likewise, the delegation demanded the cession of islands in the Gulf of Finland as well as Rybachy Peninsula. The Finns would have to lease the Hanko Peninsula for thirty years and permit the Soviets to establish a military base there. In exchange, the Soviet Union would cede Repola and Porajärvi municipalities from Eastern Karelia, an area twice the size of the territory demanded from Finland. The Soviet offer divided the Finnish government, but was eventually rejected with respect to the opinion of the public and Parliament.

On 26 November 1939, an incident was reported near the Soviet village of Mainila close to the border with Finland. A Soviet border guard post had been shelled by an unknown party resulting, according to Soviet reports, in the deaths of four and injuries of nine border guards. Research conducted by several Finnish and Russian historians later concluded that the shelling was a false flag operation carried out from the Soviet side of the border by an NKVD unit with the purpose of providing the Soviet Union with a casus belli and a pretext to withdraw from the non-aggression pact.

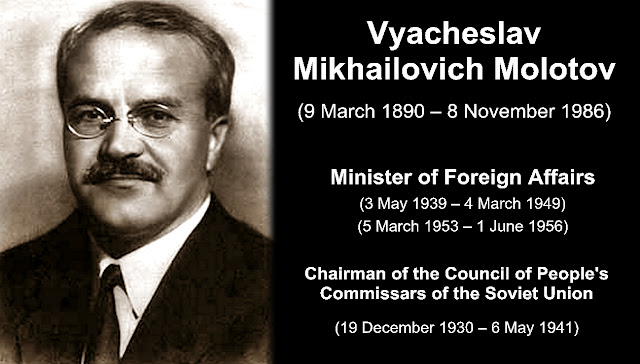

Molotov claimed that the incident was a Finnish artillery attack and demanded that Finland apologise for the incident and move its forces beyond a line 20–25 kilometers away from the border.

Finland denied responsibility for the attack, rejected the demands and called for a joint Finnish–Soviet commission to examine the incident. In turn, the Soviet Union claimed that the Finnish response was hostile, renounced the non-aggression pact and severed diplomatic relations with Finland on 28 November.

On 30 November 1939, Soviet forces invaded Finland with 21 divisions, totalling 450,000 men, and bombed Helsinki, inflicting substantial damage and casualties. In response to international criticism, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov stated that the Soviet Air Force was not bombing Finnish cities, but rather dropping humanitarian aid to the starving Finnish population,

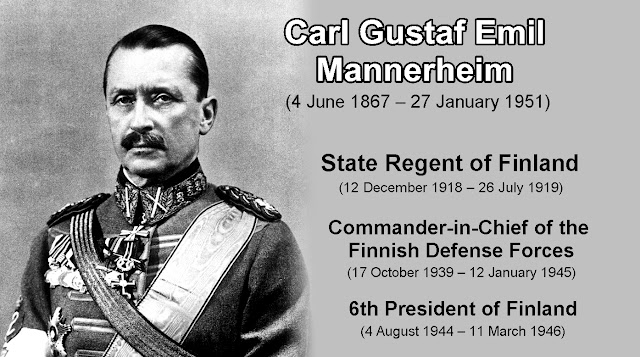

sarcastically dubbed Molotov bread baskets by Finns. Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces after the Soviet attack. Finland brought up the matter of the Soviet invasion before the League of Nations. The League expelled the USSR on 14 December 1939 and exhorted its members to aid Finland.

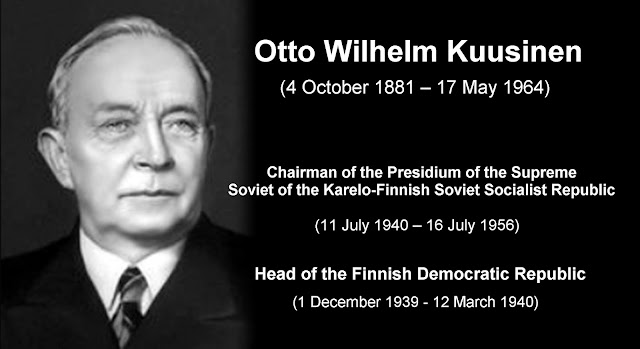

On 1 December 1939, the Soviet Union formed a puppet

government, called the Finnish Democratic Republic and headed by Otto Wille Kuusinen, in the parts of Finnish Karelia occupied by the Soviets. Kuusinen's government was also referred to as the "Terijoki Government," after the village of Terijoki, the first settlement captured by the advancing Red Army. After the war, the puppet government was disbanded. From the very outset of the war, working-class Finns stood behind the legitimate government in Helsinki. Finnish national unity against the Soviet invasion was later called the spirit of the Winter War.

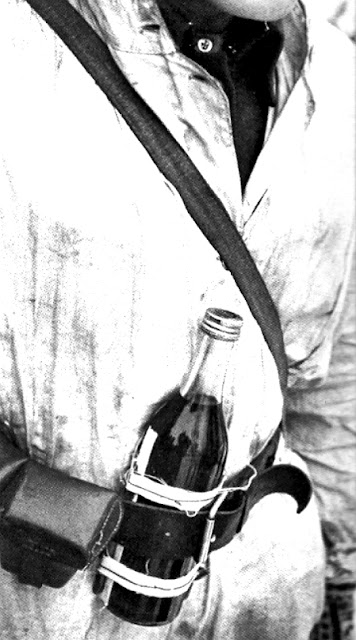

In combat, the most severe cause of confusion among Finnish soldiers was Soviet tanks. The Finns had few anti-tank weapons

and insufficient training in modern anti-tank tactics. Finns fielded a good ad hoc weapon, the Molotov cocktail, a glass bottle filled with flammable liquids and with a simple hand-lit fuse. Molotov cocktails were eventually mass-produced by the Finnish Alko alcoholic beverage corporation and bundled with matches with which to light them. 80 Soviet tanks were destroyed in the border zone engagements.

By 6 December, all of the Finnish covering forces had withdrawn to the Mannerheim Line. The Mannerheim Line, an array of Finnish defence structures, was located on the Karelian Isthmus approximately 30 to 75 kilometers from the Soviet border. The Red Army soldiers on the Isthmus numbered 250,000, facing 130,000 Finns. The Finns had built 221 strong-points along the Karelian Isthmus, mostly in the early 1920s. Many were extended in the late 1930s. Despite these defensive preparations, even the most fortified section of the Mannerheim Line had only one reinforced concrete bunker per kilometre. Overall, the line was weaker than similar lines in mainland Europe.

The Red Army began its first major attack against the Line in Taipale—the area between the shore of Lake Ladoga, the Taipale river and the Suvanto waterway. Along the Suvanto sector, the Finns had a slight advantage of elevation and dry ground to dig into. The Finnish artillery had scouted the area and made fire plans in advance, anticipating a Soviet assault. The Battle of Taipale began with a forty-hour Soviet artillery preparation. After the barrage, Soviet infantry attacked across open ground but was repulsed with heavy casualties. The assaults continued without success, and the Red Army suffered heavy losses. The Soviet advance was stopped at the Mannerheim Line and the Red Army troops suffering from poor morale and a shortage of supplies, eventually refusing to participate in more suicidal frontal attacks.

North of Lake Ladoga on the Ladoga Karelia front, the defending Finnish units relied on the terrain. Ladoga Karelia, a large forest wilderness, did not have road networks for the modern Red Army. The Soviet 8th Army had extended a new railroad line to the border, which could double the supply capability on the front. On 12 December, the advancing Soviet 139th Rifle Division, supported by the 56th Rifle Division, was defeated by a much smaller Finnish force under Paavo Talvela in Tolvajärvi, the first Finnish victory of the war.

In Central and Northern Finland, roads were few and the terrain hostile. The Finns did not expect large-scale Soviet attacks, but the

Soviets sent eight divisions, heavily supported by armour and artillery. The 155th Rifle Division attacked at Lieksa, and further north the 44th attacked at Kuhmo. The 163rd Rifle Division was deployed at Suomussalmi and ordered to cut Finland in half by advancing on the Raate road. In Finnish Lapland, the Soviet 88th and 122nd Rifle Divisions attacked at Salla. The Arctic port of Petsamo was attacked by the 104th Mountain Rifle Division by sea and land, supported by naval gunfire.

The winter of 1939–1940 was exceptionally cold with the Karelian

Isthmus experiencing a record low temperature of −43 °C on 16 January 1940. The strength of the Red Army north of Lake Ladoga in Ladoga Karelia surprised the Finnish Headquarters. The Soviets had a 3:1 advantage in manpower and a 5:1 advantage in artillery, as well as air supremacy.

In battles from Ladoga Karelia to the Arctic port of Petsamo, the Finns used guerrilla tactics. The Red Army was superior in numbers and materiel, but Finns used the advantages of speed, manoeuvre warfare and economy of force. Particularly on the Ladoga Karelia front and during the battle of Raate road, the Finns isolated smaller portions of numerically superior Soviet forces. With Soviet forces divided into smaller pieces, the Finns dealt with them individually and attacked from all sides.

On 7 December, in the middle of the Ladoga Karelian front, Finnish units retreated near the small stream of Kollaa. The

waterway itself did not offer protection, but alongside there were ridges up to 10 meters high. The ensuing battle of Kollaa lasted until the end of the war. A memorable quote, "Kollaa holds" became a legendary motto among the Finns.

The Red Army committed two divisions to the Kainuu area with orders to cross the wilderness, capture the city of Oulu and effectively cut Finland in two. There were two roads leading to Suomussalmi from the frontier: the northern Juntusranta road and the southern Raate road.

The battle of Raate road, resulted in one of the largest Soviet losses in the Winter War. The Soviet 44th and parts of the 163rd Rifle Division, comprising about 14,000 troops, were almost completely destroyed by a Finnish ambush as they marched along the forest road. The Finnish troops captured dozens of tanks, artillery pieces, anti-tank guns, hundreds of trucks, almost 2,000 horses, thousands of rifles, and much-needed ammunition and medical supplies.

In Finnish Lapland, the forests gradually thin out until in the north there are no trees at all. Thus, the area offers more room for tank deployment, but it is vastly underpopulated and experiences copious snowfall. To the north was Finland's only ice-free port in the Arctic, Petsamo. The Finns did not have the manpower to defend it fully as the main front was south at the Karelian Isthmus. In the battle of Petsamo, the Soviet 104th Division attacked the

Finnish 104th Independent Cover Company. The Finns gave up Petsamo and concentrated on delaying actions. The area was treeless, windy, and relatively low, offering little defensible terrain. During the winter, the Finns in Lapland had the advantage of almost constant darkness and extreme temperatures. The Finns executed guerrilla attacks against Soviet supply lines and patrols. As a result, the Soviet movements were halted by the efforts of one-fifth as many Finns.

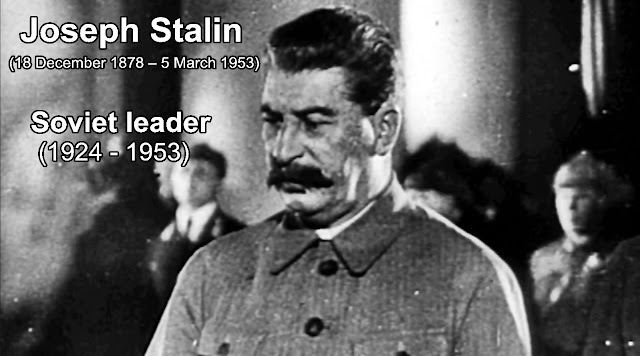

Joseph Stalin was not pleased with the results of December in the Finnish campaign. The Red Army had been humiliated. By the third week of the war, Soviet propaganda was working hard to explain the failures of the Soviet military to the populace: blaming bad terrain and harsh climate, and falsely claiming that the Mannerheim Line was stronger than the Maginot Line, and that the Americans had sent 1,000 of their best pilots to Finland.

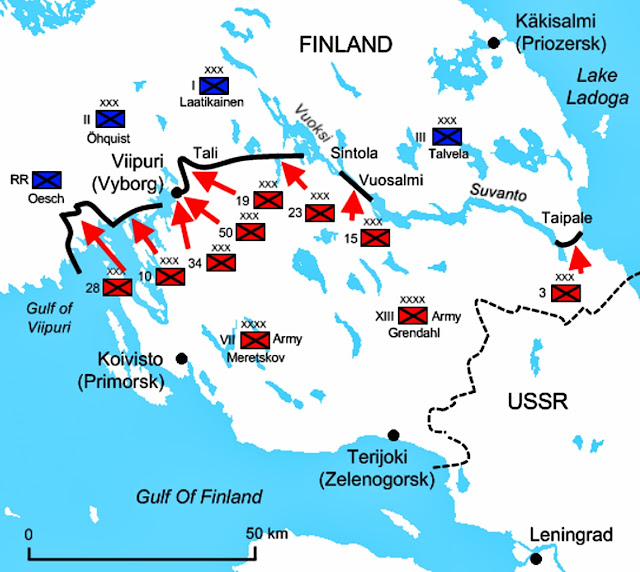

The main focus of the Soviet attack was switched to the Karelian Isthmus. The 7th Army, now under Kirill Meretskov, would

concentrate 75 percent of its strength against the 16 kilometers stretch of the Mannerheim Line between Taipale and the Munasuo swamp. The Soviets shipped large numbers of new tanks and artillery pieces to the theatre. Troops were increased from ten divisions to 25–26 divisions with six or seven tank brigades and several independent tank platoons as support, totalling 600,000 soldiers. On 1 February, the Red Army began a large offensive, firing 300,000 shells into the Finnish line in the first 24 hours of the bombardment.

During daylight hours, the Finns took shelter inside their fortifications from the bombardments and repaired damage during

the night. The situation led quickly to war exhaustion among the Finns, who lost over 3,000 soldiers in trench warfare. The Soviets also made occasional small infantry assaults with one or two companies. Because of the shortage of ammunition, Finnish artillery emplacements were under orders to fire only against directly threatening ground attacks.

After 10 days of constant artillery barrage, the Soviets achieved a breakthrough on the Western Karelian Isthmus in the second battle of Summa.

On 11 February, the Soviets had approximately 460,000 soldiers, 3,350 artillery pieces, 3,000 tanks and 1,300 aircraft deployed on the Karelian Isthmus. The Red Army was constantly receiving new

recruits after the breakthrough. Opposing them, the Finns had eight divisions, totalling about 150,000 soldiers. One by one, the defenders' strongholds crumbled under the Soviet attacks and the Finns were forced to retreat. On 15 February, Mannerheim authorised a general retreat to a fallback line of defence. On the eastern side of the isthmus, the Finns continued to resist Soviet assaults, repelling them in the battle of Taipale.

On 5 March, the Red Army advanced 10 to 15 kilometers past the Mannerheim Line and entered the suburbs of Vyborg. The same day, the Red Army established a beachhead on the Western Gulf of Vyborg. The Finns proposed an armistice on 6 March, but the Soviets, wanting to keep the pressure on the Finnish government, declined the offer. The Finnish peace delegation travelled to Moscow via Stockholm and arrived on 7 March. The USSR made further demands as their military position was strong and improving. On 9 March, the Finnish military situation on the Karelian Isthmus was dire as troops were experiencing heavy casualties. Artillery ammunition was exhausted and weapons were wearing out. The Finnish government, noting that the hoped-for Franco-British military expedition would not arrive in time, as Norway and Sweden had not given the Allies right of passage, had little choice but to accept the Soviet terms.

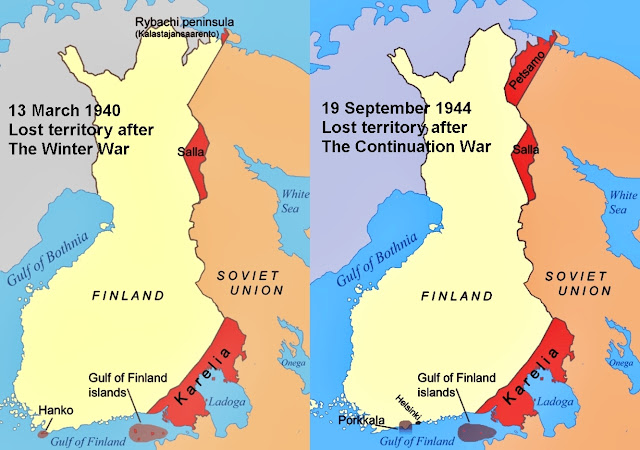

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed in Moscow on 12 March 1940. A cease-fire took effect the next day at noon Leningrad time, 11 a.m. Helsinki time. With it, Finland ceded a portion of Karelia, the entire Karelian Isthmus as well as a large swath of land north of Lake Ladoga. The area included Finland's second largest city of Vyborg, much of Finland's industrialised territory, and significant parts still held by Finland's military—all in all, 11 percent of the territory and 30 percent of the economic assets of pre-war Finland. Twelve percent of Finland's population, 422,000 Karelians, were

evacuated and lost their homes. Finland ceded a part of the region of Salla, Rybachy Peninsula in the Barents Sea, and four islands in the Gulf of Finland. The Hanko peninsula was leased to the Soviet Union as a military base for 30 years. The region of Petsamo, captured by the Red Army during the war, was returned to Finland according to the treaty.

The 105-day war had a profound and depressing effect in Finland. Helsinki officially announced 19,576 dead immediately after the war. According to revised estimates in 2005 by Finnish historians, 25,904 people died or went missing and 43,557 were wounded on the Finnish side during the war. The official Soviet figure in 1940 for their dead was 48,745. More recent Russian estimates vary from 53,500 dead to 391,783 total casualties with 188,671 wounded.