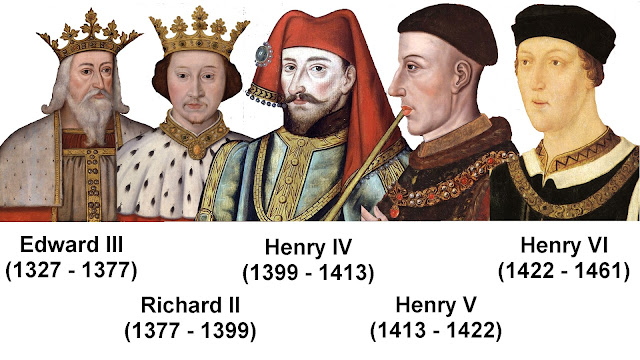

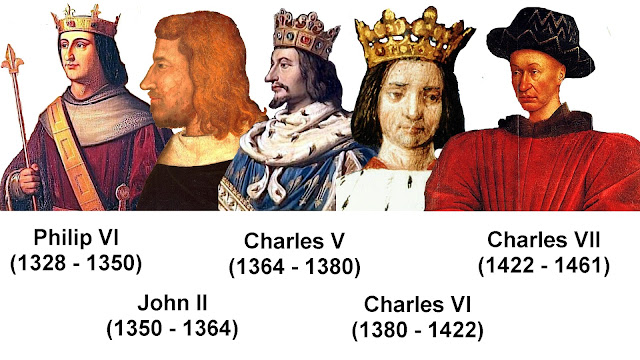

The Hundred Years' War is the modern term for a series of conflicts between England and France over succession to the French throne. It lasted from 1337 to 1453, so it might more accurately be called the "116 Years' War." It was one of the most notable conflicts of the Middle Ages, in which five generations of kings from two rival dynasties, House of Plantagenet, rulers of the Kingdom of England and House of Valois, rulers of the Kingdom of France fought for the throne of the largest kingdom in Western Europe. The war marked both the height of chivalry and its subsequent decline, and the development of strong national identities in both countries.

The Hundred Years' War was divided into four phases separated by truces: the Edwardian Era War (1337–1360), ended with English victory; the Caroline War (1369–1389), ended with French victory; The 1st phase of the Lancastrian War (1415–1420), ended with English victory; and The 2nd phase of the Lancastrian War (1420–1453), ended with French victory.

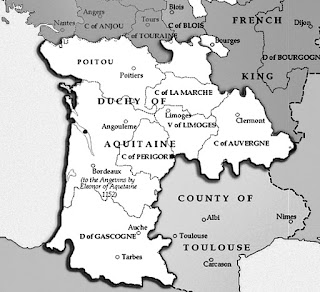

Tensions between the English and French thrones over continental land dated to 1066 when William, Duke of Normandy, conquered England. His descendants in England had gained further lands in France by the reign of Henry II, who inherited the County of Anjou from his father and control of the Dukedom of Aquitaine through his wife. Tensions simmered between the growing power of the French kings and the great power of their most powerful, and in some eyes equal, English royal vassal, occasionally leading to armed conflict.

King John of England lost Normandy, Anjou and other lands in France in 1204, and his son was forced to sign the Treaty of Paris ceding this land. In return he received Aquitaine and other territory to be held as a vassal of France. This was one king bowing to another, and there were further wars in 1294 and 1324, when Aquitaine was confiscated by France and won back by the English crown. As the profits from Aquitaine alone rivalled those of England, the region was important, and retained many differences from the rest of France.

The outbreak of war was motivated by a gradual rise in tension between the Kings of France and England about Guyenne, Flanders and Scotland. The dynastic question, which arose due to an interruption of the direct male line of the Capetians, was the official pretext.

Charles IV of France, the last direct Capetian King of France and King of Navarre, died in 1328, leaving a daughter and a pregnant wife. If the unborn child was male, he would become king; if not, Charles left the choice of his successor to the nobles.

By proximity of blood, the nearest male relative of Charles IV was his nephew Edward III of England. Edward was the son of Isabella, the sister of the dead Charles IV, but the question arose whether she should be able to transmit a right to inherit that she did not herself possess. The assemblies of the French barons and prelates and the University of Paris decided that males who derive their right to inheritance through their mother should be excluded. Thus the nearest heir through male ancestry was Charles IV's first cousin, Philip, Count of Valois, and it was decided that he should be crowned Philip VI.

Edward III reluctantly recognized Philip VI and paid him homage for his French fiefs. He made concessions in Guyenne, but reserved the right to reclaim territories arbitrarily confiscated. After that, he expected to be left undisturbed while he made war on Scotland. In 1326 Charles IV renewed the treaty with Scotland, promising support if England will invade them. Similarly, the French would find Scottish support if their own kingdom was attacked.

Philip VI assembled a large naval fleet in 1336, threatening England. To deal with this crisis, Edward proposed that the English raise two armies, one to deal with the Scots "at a suitable time", the other to proceed at once to Gascony. At the same time ambassadors were to be sent to France with a proposed treaty for the French king. At the end of April 1337, Philip of France was invited to meet the delegation from England but refused. Then, in May 1337, Philip met with his Great Council in Paris. It was agreed that the Duchy of Aquitaine, effectively Gascony, should be taken back into the king's hands on the grounds that Edward the 3rd was in breach of his obligations as vassal and had sheltered the king's 'mortal enemy' Robert d'Artois. Edward responded to the confiscation of Aquitaine by challenging Philip's right to the French throne.

This was the beginning of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War – the Edwardian War (1337–1360).

Edward, with his fleet, sailed from England on 22 June 1340, and arrived the next day off the Zwyn estuary. The French fleet assumed a defensive formation off the port of Sluis. The English fleet apparently tricked the French into believing they were withdrawing. However, when the wind turned in the late afternoon, the English attacked with the wind and sun behind them. The French fleet was almost completely destroyed in what became known as the Battle of Sluys. England dominated the English Channel for the rest of the war, preventing French invasions.

After the battle of Sluys, Edward III landed in Normandy in July 1346 with about 10,000 men. The English army captured the completely unguarded Caen in just one day, surprising the French. Philip gathered a large army to oppose Edward, who chose to march northward toward the Low Countries, pillaging as he went, rather than attempting to take and hold territory. The battle was fought on 26 August 1346 near Crécy, in northern France. An army of English, Welsh, and allied troops from the Holy Roman Empire led by Edward the 3rd of England, engaged and defeated a much larger army of French, Genoese and Majorcan troops led by Philip VI of France. The French vanguard made contact and started to attack without the benefit of a plan. The French made as many as 15 attacks and the English checked each one in turn mainly because of the English longbowmen. At the end, the French were decimated and the English had a decisive victory. From an army of 30,000 men, the French had 2,000 men-at-arms killed.

The battle crippled the French army's ability to come to the aid of Calais, which was besieged by Edward's army the following month. Calais fell after a year-long siege and became an exclave of England, remaining under English rule until 1558.

In 1348, the Black Death began to ravage Europe. The population of France decreased from 16 to 12 million, while population of England decreased from 4 to 2 million.

In 1356, after the plague had passed and England was able to recover financially, Edward's son and namesake, the Prince of Wales, later known as the Black Prince, invaded France from Gascony, winning a great victory in the Battle of Poitiers on 19 September. French army lost 2,500 soldiers killed, and 2,000 captured, including king John the 2nd and many of his nobles. With John held hostage, his son the Dauphin (later to become Charles V of France) assumed the powers of the king as regent.

Edward wanted the crown and chose the cathedral city of Reims for his coronation. Reims was the traditional coronation city. Edward besieged the city for five weeks, but the defences held and there was no coronation.

On Easter Monday April 13 1360, Edward's army arrived at the gates of Chartres. The French defenders refused battle, instead sheltering behind their fortifications, and a siege ensued. That night a huge hail storm struck and killed an estimated 1,000 Englishmen and up to 6,000 horses. The storm was so devastating that it caused more English military casualties than any of the previous battles of the war. Edward III of England was convinced the phenomenon was a sign from God against his endeavors.

On May 8, 1360, three weeks later, the Treaty of Brétigny was signed, marking the end of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War. In return for increased lands in Aquitaine, Edward renounced Normandy, Touraine, Anjou and Maine and set King John's ransom at 3 million crowns. Edward also abandoned his claim to the crown of France. In 1364, John II died in London, while still in honourable captivity. Charles the V succeeded him as king of France.

In May 1369, the Black Prince, son of Edward III of England, received summons from the French king demanding his presence in Paris. The Black Prince answered that he would go to Paris with sixty thousand men behind him. War broke out again and Edward the III resumed the title of King of France, while Charles V declared that all the English possessions in France were forfeited.

This was the beginning of the second phase of the Hundred Years' War – the Caroline War (1369–1389), so-named after Charles the V of France, who resumed the war nine years after the Treaty of Brétigny.

With his health continuing to deteriorate, the Black Prince returned to England in January 1371, where by now his father Edward the III was elderly and also in poor health. The prince's illness was debilitating, and he died on 8 June 1376. Edward the 3rd died the following year on 21 June 1377. He was succeeded by the Black Prince's second son Richard the II, who was still a child.

Richard faced many challenges during his reign, including the Peasants' Revolt led by Wat Tyler in 1381 and an Anglo-Scottish war in 1384–85. His attempts to raise taxes to pay for his Scottish adventure and for the protection of Calais against the French made him increasingly unpopular.

Charles the V resumed the war in favorable conditions. France, after all, was still the foremost kingdom in Western Europe. French army continued a series of careful campaigns, avoiding major English field forces, but capturing town after town, including Poitiers in 1372 and Bergerac in 1377.

In 1372, English command of the sea, which had been kept since the Battle of Sluys, came to an end by their disastrous defeat by a joint Franco-Castilian fleet at the Battle of La Rochelle in the Bay of Biscay. This defeat undermined English seaborne trade and supplies and isolated their Gascon possessions. By the time of Charles V death in 1380, the English only held Calais. Charles V was succeeded by his underage son, Charles the VI, who was placed under the joint regency of his three uncles.

Charles VI, made peace with the son of the Black Prince, Richard II, in 1389. This truce was extended many times until the war was resumed in 1415. In the meantime Charles VI of France was descending into madness and an open conflict for power began between his cousin John the Fearless and his brother, Louis of Orléans.

The domestic and dynastic difficulties faced by England and France in this period quieted the war for a decade. Henry the IV of England died in 1413 and was replaced by his eldest son Henry the V. Charles VI of France's mental illness allowed his power to be exercised by royal princes whose rivalries caused deep divisions in France. Henry V was well aware of these divisions and hoped to exploit them.

Henry V made territorial claims in France, and also demanded the hand of Charles VI's youngest daughter Catherine of Valois. The French rejected his demands, leading Henry to prepare for war.

This was the beginning of the 3rd phase of the war, Lancastrian War (1415–1453), who can also be divided in 2 phases.

In August 1415, Henry V sailed from England with a force of about 10,500 and laid siege to Harfleur. After the city surrendered on 22 September 1415, Henry started a raiding expedition across France toward English-occupied Calais. During his march the French army of 20,000 was able to position itself between Henry and Calais, near Agincourt, north of the Somme. Henry used a narrow front channeled by woodland to give his heavily outnumbered force a chance. The French deployed in three lines. The first line of French knights attacked only to be repulsed by the English longbowmen. The second line attacked and was beaten back, their charge bogged down by the mud on the field. The third line moved to engage but lost heart when they crossed the field covered with French dead; they soon retreated. Henry was left with control of the battlefield and a decisive victory.

Henry ordered the slaughter of what were perhaps several thousand French prisoners, sparing only the most high ranked. According to most chroniclers, Henry's fear was that the prisoners who outnumbered their captors would realize their advantage in numbers, rearm themselves with the weapons strewn about the field and overwhelm the exhausted English forces.

Henry retook much of Normandy, including Caen in 1417, and Rouen on 19 January 1419, turning Normandy English for the first time in two centuries. A formal alliance was made with the Duchy of Burgundy, which had taken Paris after the assassination of Duke John the Fearless in 1419. In 1420, Henry met with King Charles VI. They signed the Treaty of Troyes, by which Henry finally married Charles' daughter Catherine of Valois and Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France. The Dauphin, Charles VII, was declared illegitimate.

Henry V of England died on 31 August 1422, leaving only one heir, his nine-month-old son, Henry, later to become Henry VI. Also, the elderly and insane Charles VI of France died two months later, on 21 October 1422. The war in France continued with English victories. The English won an emphatic victory at the Battle of Verneuil, (17 August 1424). The archers fought to devastating effect against the Franco-Scottish army. The effect of the battle was to virtually destroy the Dauphin's field army and to eliminate the Scots as a significant military force for the rest of the war.

Everything changed after appearance of Joan of Arc. Joan of Arc (1412-1431) nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans", said she received visions of the Archangel Michael, Saint Margaret, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria instructing her to support CharlesVII and recover France from English domination. The uncrowned King Charles VII sent Joan to the siege of Orléans as part of a relief mission. She gained prominence after the siege was lifted only nine days later.

Inspired by Joan, the French took several English strongholds on the Loire. The English retreated from the Loire Valley, pursued by a French army. Near the village of Patay, French cavalry broke through a unit of English longbowmen that had been sent to block the road, then swept through the retreating English army. The English lost 2,200 men, and the commander, John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, was taken prisoner. This victory opened the way for the Dauphin to march to Reims for his coronation as Charles VII, on 16 July 1429.

Manwhile, Henry VI was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey on 5 November 1429 and king of France at Notre-Dame, in Paris, on 16 December 1431. Joan of Arc was captured by the Burgundians at the siege of Compiegne on 23 May 1430. The Burgundians transferred her to the English, who organised a trial headed by Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais and member of the English Council at Rouen. Joan was convicted and burned at the stake on 30 May 1431. In 1456, an inquisitorial court authorized by Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, debunked the charges against her, pronounced her innocent, and declared her a martyr.

After the death of Joan of Arc, the fortunes of war turned dramatically against the English. In September 1435 , Philip III, duke of Burgundy, deserted to Charles VII, signing the Treaty of Arras that returned Paris to the King of France. This was a major blow to English sovereignty in France.

The long truces that marked the war gave Charles time to centralise the French state and reorganise his army and government, replacing his feudal levies with a more modern professional army that could put its superior numbers to good use. A castle that once could only be captured after a prolonged siege would now fall after a few days from cannon bombardment. The French artillery developed a reputation as the best in the world.

In 1449, an English force sacked and looted Fougères in Brittany. Charles VII, declared himself no longer bound by the terms of the truce. His forces rapidly overran Normandy during 1449-1450. After French victory at Rouen in October 1449, Charles VII continues the French offensive and presses the English back into the town of Formigny. On 15 April 1450, French artillary blasts away at most of the English army and the English are badly defeated losing more than 4,000 men out of a force of 5,000. With no other significant English forces in Normandy, the whole region quickly fell to the victorious French.

After Charles VII successful Normandy campaign in 1450, he concentrated his efforts on Gascony, the last province held by the English. Bordeaux, Gascony's capital, was besieged and surrendered to the French on 30 June 1451. Largely due to the English sympathies of the Gascon people, this was reversed when John Talbot and his army retook the city on 23 October 1452. However, the English were decisively defeated at the Battle of Castillon on 17 July 1453, losing 4,000 men. English authority in Gascony eroded and the French retook Bordeaux on 19 October 1453.

Henry VI of England lost his mental capacity in late 1453, which led to the outbreak of the Wars of the Roses in England. The English Crown lost all its continental possessions except for the Pale of Calais, which was the last English possession in mainland France, and the Channel Islands, historically part of the Duchy of Normandy and thus of the Kingdom of France. Calais was finally lost in 1558, while The Channel Islands have remained British Crown Dependencies.

England and France remained formally at war for another 20 years until the Treaty of Picquigny (1475). The treaty formally ended the Hundred Years' War with Edward renouncing his claim to the throne of France. However, future Kings of England (and later of Great Britain) continued to claim the title until 1803, when they were dropped in deference to the exiled Count of Provence, titular King Louis XVIII of France, who was living in England after the French Revolution.