Monday, April 10, 2023

The Angevin Empire in England and Western France

The Angevin Empire describes the possessions of the Angevin kings of England who held lands in England and France during the 12th and 13th centuries. Its rulers were Henry II (1154–1189), Richard the Lionheart (1189–1199), and John (1199–1216).

The Angevins were a royal house having its origin in the county of Anjou in the west of France. In the 10 years from 1144, two successive counts of Anjou in France, Geoffrey and his son, the future Henry II, won control of a vast assemblage of lands in western Europe that would last for 80 years and would retrospectively be referred to as the Angevin Empire. As a political entity this was structurally different from the preceding Norman and subsequent Plantagenet realms.

Geoffrey became Duke of Normandy in 1144 and died in 1151. In 1152 his heir, Henry, added

Aquitaine by virtue of his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. Henry also inherited the claim of his

mother, Empress Matilda, the daughter of King Henry I, to the English throne, to which he succeeded

in 1154 following the death of King Stephen.

During the early years of his reign, Henry II restored the royal administration in England, re-

established hegemony over Wales and gained full control over his lands in Anjou, Maine and Touraine. Henry's desire to reform the relationship with the Church led to conflict with his former friend Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. This controversy lasted for much of the 1160s and resulted in Becket's murder in 1170.

The influence and power of the House of Anjou brought them into conflict with the kings of France of the House of Capet, to whom they also owed feudal homage to their French possessions, bringing in a period of rivalry between both dynasties.

At that time King of France was Louis VII. Louis VII led an ineffective war against Henry for having married without the authorization of his suzerain. The result was a humiliation for the enemies of Henry and Eleanor. In spite of Louis understanding the danger of the growing Angevin power, through indecision and a lack of fiscal and military resources in comparison to Henry II, he failed to oppose Angevin hegemony effectively.

Henry expanded his empire, at Louis' expense, taking Brittany and pushing east into central France and south into Toulouse, while the two rulers fought what has been termed a "cold war" over several decades.

Henry and Eleanor had eight children—three daughters and five sons. Three of his sons would be king, though Henry the Young King was named his father's co-ruler rather than a stand-alone king.

As the sons grew up, tensions over the future inheritance of the empire began to emerge, encouraged by Louis and his son King Philip II. In 1173 Henry's heir apparent, "Young Henry", rebelled in protest; he was joined by his brothers Richard (later a king) and Geoffrey and by their mother, Eleanor. France, Scotland, Brittany, Flanders, and Boulogne allied themselves with the rebels. The Great Revolt was only defeated by Henry's vigorous military action and talented local commanders, many of them "new men" appointed for their loyalty and administrative skills.

Young Henry and Geoffrey revolted again in 1183, resulting in Young Henry's death. The Norman invasion of Ireland provided lands for his youngest son John (later a king), but Henry struggled to find ways to satisfy all his sons' desires for land and immediate power. By 1189, Young Henry and Geoffrey were dead, and Philip successfully played on Richard's fears that Henry II would make John king, leading to a final rebellion. Richard paid homage to Philip for the continental lands his father held then they attacked Henry together. Decisively defeated by Philip and Richard and suffering from a bleeding ulcer, Henry II retreated to Chinon castle in Anjou. He died soon afterwards and was succeeded by Richard.

Richard I was officially invested as Duke of Normandy on 20 July 1189 and crowned king in Westminster Abbey on 3 September 1189.

Richard was one of the leaders of the Third Crusade against Saladin, which never actually succeeded. King Richard and King Philip left in 1190, traveling together to Sicily. They quarreled most of the time, and then they separated, Filip leaving for Accra, and Richard stopped in Cyprus. In May 1191, Richard quarreled with the local ruler and conquered the island. He fought in the Battle of Acre and the Battle of Arsuf. In the end, as he was unable to win back Jerusalem from the Muslims, he decided to return home to England in October 1192.

King Richard left the Holy Land over a year later than Philip, and possibly could have retrieved his empire intact had he reached France soon after. However, during the crusade Leopold V, Duke of Austria, had been insulted by Richard, and so he arrested Richard near Vienna, on his journey home.

When word reached Philip that Richard had been captured on his way back from the Holy Land, he promptly invaded Normandy, reaching as far as Dieppe, and laid siege to Rouen, the ducal capital of Normandy.

In January 1193, Richard's brother, John, was summoned to Paris, where he did homage to Philip for all of Richard's lands, and promised to marry Alys with Artois as her dowry. In return, the Vexin and the castle of Gisors would be given to Philip. With the help of Philip, John went to invade England and incite rebellion against Richard's justiciars. John failed and then had worse luck when it was discovered Richard was alive, which was unknown until this point.

To prevent Richard from spoiling their plans, Philip and John attempted to bribe Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI in order to keep the English king captive for a little while longer. Henry refused, and Richard was released from captivity on 4 February 1194. By 13 March Richard had returned to England, and by 12 May he had set sail for Normandy with some 300 ships, eager to engage Philip in war.

John betrayed Philip by murdering the garrison of Évreux and handing the town down to Richard. The first part of this war was difficult for Richard who suffered several setbacks. After Philip was abandoned by some of his vassals, things changed and his army suffered a serious defeat at Gisors near Paris. By autumn 1198, Richard had regained almost all that had been lost in 1193. In desperate circumstances, Philip offered a truce so that discussions could begin towards a more permanent peace, with the offer that he would return all of the territories except for Gisors.

Richard accepted the truce in January 1199, and in Aquitaine he held more territories than he had before the war. Richard I had to deal with a revolt once again, but this time from Limousin. He was struck by a bolt in April 1199 at Châlus-Chabrol and died of a subsequent infection.

Richard produced no legitimate heirs and was succeeded by his brother John as King of England. He came to an agreement with Philip II of France to recognise John's possession of the continental Angevin lands at the peace treaty of Le Goulet in 1200.

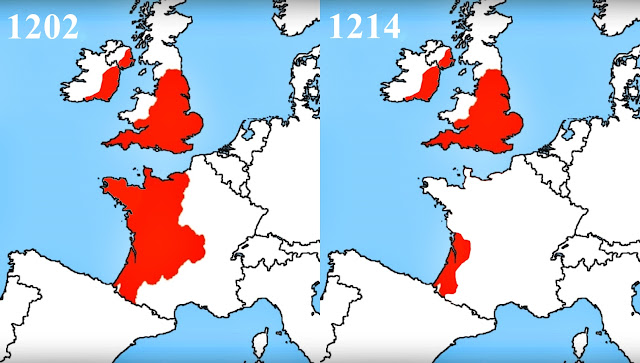

When war with France broke out again in 1202, John achieved early victories, but shortages of military resources and his treatment of Norman, Breton, and Anjou nobles resulted in the collapse of his empire in northern France in 1204. He spent much of the next decade attempting to regain these lands, raising huge revenues, reforming his armed forces and rebuilding continental alliances. His judicial reforms had a lasting effect on the English common law system, as well as providing an additional source of revenue.

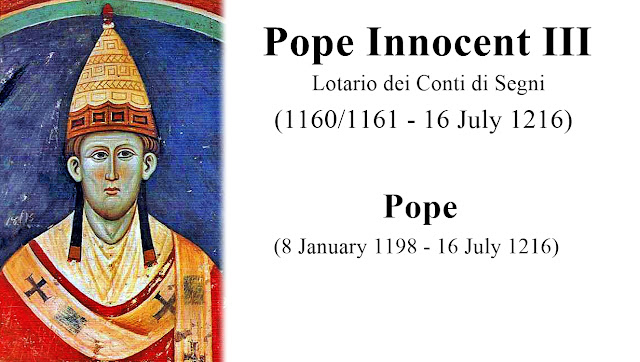

An argument with Pope Innocent III led to John's excommunication in 1209, a dispute he finally settled in 1213. John's attempt to defeat Philip in 1214 failed due to the French victory over John's allies at the battle of Bouvines. Philip's victory was crucial to the political order in England and France, and the battle was instrumental in establishing absolute monarchy in France. John lost control of most of his continental possessions, apart from Gascony in southern Aquitaine. This defeat set the

scene for further conflicts between England and France, leading up to the Hundred Years' War.

When he returned to England, John faced a rebellion by many of his barons, who were unhappy with his fiscal policies and his treatment of many of England's most powerful nobles. Although both John and the barons agreed to the Magna Carta peace treaty in 1215, neither side complied with its

conditions. Civil war broke out shortly afterwards, with the barons aided by Louis VIII of France. It soon descended into a stalemate. John died of dysentery contracted whilst on campaign in eastern England during late 1216. Supporters of his son Henry III went on to achieve victory over Louis and the rebel barons the following year.

Many historians use John's death and William Marshall's appointment as protector of nine-year-old Henry III to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty. Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power during the 13th century marked a "turning point in European history".