inhabited region of Ionia in 547 BC. Struggling to rule the independent-minded cities of Ionia, the Persians appointed tyrants to rule each of them. This would prove to be the source of much trouble for the Greeks and Persians alike.

In 499 BC, the tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, embarked on an

expedition to conquer the island of Naxos, with Persian support; however, the expedition was a debacle and, pre-empting his dismissal, Aristagoras incited all of Hellenic Asia Minor into rebellion against the Persians. This was the beginning of the Ionian Revolt, which would last until 493 BC, progressively drawing more regions of Asia Minor into the conflict. Aristagoras secured military support from Athens and Eretria, and in 498 BC these

forces helped to capture and burn the Persian regional capital of Sardis. The Persian king Darius the Great vowed to have revenge on Athens and Eretria for this act. The revolt continued, with the two sides effectively stalemated throughout 497–495 BC. In 494

BC, the Persians regrouped, and attacked the epicentre of the revolt in Miletus. At the Battle of Lade, the Ionians suffered a decisive defeat, and the rebellion collapsed, with the final members being stamped out the following year.

Seeking to secure his empire from further revolts and from the interference of the mainland Greeks, Darius embarked on a scheme to conquer Greece and to punish Athens and Eretria for the burning of Sardis. The first Persian invasion of Greece began in 492 BC, with the Persian general Mardonius successfully re-subjugating Thrace and conquering Macedonia before several mishaps forced an early end to the rest of the campaign.

In 490 BC a second force was sent to Greece, this time across the Aegean Sea, under the command of Datis and Artaphernes. This expedition subjugated the Cyclades, before besieging, capturing and razing Eretria.

Then a Persian army of 25,000 men landed unopposed on the Plain of Marathon, and the Athenians appealed to Sparta to join forces against the invader. Owing to a religious festival, the Spartans were detained, and the 10,000 Athenians had to face the Persians aided only by 1,000 men from Plataea. The Athenians were commanded by 10 generals, the most daring of whom was Miltiades. While the

Persian cavalry was away, he seized the opportunity to attack. The Greeks won a decisive victory, losing only 192 men to the Persians’ 6,400, according to the historian Herodotus. The Greeks then prevented a surprise attack on Athens itself by quickly marching back to the city.

Darius then began to plan to completely conquer Greece, but died in 486 BC and responsibility for the conquest passed to his son Xerxes. In 480 BC, Xerxes personally led the second Persian invasion of Greece with one of the largest ancient armies ever assembled.

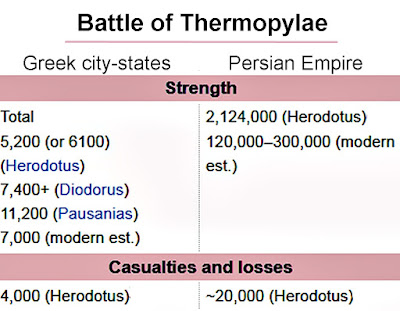

The Greeks decided to deploy a force of about 7,000 men at the narrow pass of Thermopylae and a force of 271 ships under Themistocles at Artemisium. Xerxes’ forces advanced slowly toward the Greeks, suffering losses from the weather. The Persians attacked the Greeks at Thermopylae for two days but suffered

heavy losses. However, on the second night a Greek traitor guided

the best Persian troops around the pass behind the Greek army. The Spartan general Leonidas dispatched most of the Greeks south to safety but fought to the death at Thermopylae with the Spartan and Thespian soldiers who remained. While the battle raged at Thermopylae, the Persian fleet attacked the Greek navy, with both sides losing many ships. Xerxes’ army, aided by northern Greeks who had joined it, marched south.

In September the Persians burned Athens, which, however, by that time had been evacuated. In the meantime, the Greeks decided to

station their fleet in the Strait of Salamis. Themistocles devised a clever stratagem: feigning retreat, he lured the Persian fleet into the narrow strait. The Persians were then outmaneuvered and badly beaten by the Greeks’ ships in the ensuing naval battle. Soon afterward, the Persian navy retreated to Asia.

After Salamis, Xerxes returned home to his palace at Sousa but he left the gifted general Mardonius in charge of the invasion which was still very much on. The Persian position remained strong despite the naval defeat - they still controlled much of Greece and

their large land army was intact. After a series of political negotiations, it became clear that the Persians would not gain victory on land through diplomacy and the two opposing armies met at Plataea in Boeotia in August 479 BC. The Greeks refused to be drawn into the prime cavalry terrain around the Persian camp, resulting in a stalemate that lasted 11 days. While attempting a retreat after their supply lines were disrupted, the Greek battle line fragmented. Thinking the Greeks in full retreat, Mardonius ordered his forces to pursue them, but the Greeks halted and gave battle, routing the lightly armed Persian infantry and killing Mardonius. After this the Persian force dissolved in rout. 40,000 troops managed to escape via the road to Thessaly, but the rest fled to the Persian camp where they were trapped and slaughtered by the Greeks, finalising the Greek victory.

Herodotus recounts that, on the afternoon of the Battle of Plataea, a

rumour of their victory at that battle reached the Allies' navy, at that time off the coast of Mount Mycale in Ionia. Their morale boosted,

the Allied marines fought and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Mycale that same day, destroying the remnants of the Persian fleet, crippling Xerxes's sea power, and marking the ascendancy of the Greek fleet.

The Greeks then expelled the Persian garrisons from Sestos in 479 BC and Byzantium in 478 BC. The actions of the general Pausanias, who was suspected of conspiring with the Persians at the siege of Byzantium, alienated many of the Greek states from the Spartans, and the anti-Persian alliance was therefore reconstituted around Athenian leadership, called the Delian League. The Delian League continued to campaign against Persia for the next three decades, beginning with the expulsion of the remaining Persian garrisons from Europe. At the Battle of the Eurymedon in 466 BC, the League won a double victory that finally secured freedom for the cities of Ionia. However, the League's involvement in an Egyptian revolt from 460–454 BC resulted in a disastrous defeat, and further campaigning was suspended. A Greek fleet was sent to Cyprus in 451 BC, but achieved little, and when it withdrew the Greco-Persian Wars drew to a quiet end. Some historical sources suggest the end of hostilities was marked by a peace treaty between Athens and Persia, the Peace of Callias.