Monday, April 3, 2023

The Spartacus War (73–71 BC)

The revolt of the gladiator Spartacus in 73-71 BC remains the most successful slave revolt in the history of Rome. The rebellion is known as the Third Servile War and was the last of three major slave revolts which Rome suppressed.

With Rome's heavy involvement in wars of conquest in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, tens if not hundreds of thousands of slaves at a time were imported into the Roman economy from various European and Mediterranean acquisitions. While there was limited use for slaves as servants, craftsmen, and personal attendants, vast numbers of slaves worked in mines and on the agricultural lands of Sicily and southern Italy.

For the most part, slaves were treated harshly and oppressively during the Roman republican period. Under Republican law, a slave was not considered a person, but property. Owners could abuse, injure or even kill their own slaves without legal consequence.

This high concentration and oppressive treatment of the slave population led to rebellions. In 135 BC and 104 BC, the First and Second Servile Wars, respectively, erupted in Sicily, where small bands of rebels found tens of thousands of willing followers wishing to escape the oppressive life of a Roman slave. While these were considered serious civil disturbances by the Roman Senate, taking years and direct military intervention to quell, they were never considered a serious threat to the Republic. The Roman heartland had never seen a slave uprising, nor had slaves ever been seen as a potential threat to the city of Rome. This would all change with the Third Servile War.

In the Roman Republic of the 1st century, gladiatorial games were one of the more popular forms of entertainment. In order to supply gladiators for the contests, several training schools, or ludi, were established throughout Italy. In these schools, prisoners of war and condemned criminals—who were considered slaves—were taught the skills required to fight in gladiatorial games. In 73 BC, a group of some 200 gladiators in the Capuan school owned by Lentulus Batiatus plotted an escape. When their plot was betrayed, a force of about 70 men seized kitchen implements, ("choppers and spits"), fought their way free from the school, and seized several wagons of gladiatorial weapons and armor.

Once free, the escaped gladiators chose Spartacus and two Gallic slaves—Crixus and Oenomaus—as their leaders. Although Roman authors assumed that the escaped slaves were a homogeneous group with Spartacus as their leader, they may have projected their own hierarchical view of military leadership onto the spontaneous organization, reducing other slave leaders to subordinate positions in their accounts.

Spartacus was "a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator". Spartacus was trained at the gladiatorial school (ludus) near Capua belonging to Lentulus Batiatus. He was a heavyweight gladiator called a murmillo.

After their escape, Spartacus and his men defeated legions sent after them, plundered the region surrounding Capua, recruited many other slaves into their ranks, and eventually retired to a more defensible position on Mount Vesuvius.

The response of the Romans was hampered by the absence of the Roman legions, which were already engaged in fighting a revolt in Spain and the Third Mithridatic War. Furthermore, the Romans considered the rebellion more of a policing matter than a war. Rome dispatched militia under the command of praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber, which besieged Spartacus and his camp on Mount Vesuvius, hoping that starvation would force Spartacus to surrender. They were surprised when Spartacus, who had made ropes from vines, climbed down the cliff side of the volcano with his men and attacked the unfortified Roman camp in the rear, killing most of them.

The rebels also defeated a second expedition, nearly capturing the praetor commander, killing his lieutenants and seizing the military equipment.With these successes, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, as did "many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region", swelling their ranks to some 70,000.

In these altercations Spartacus proved to be an excellent tactician, suggesting that he may have had previous military experience. Though the rebels lacked military training, they displayed a skillful use of available local materials and unusual tactics when facing the disciplined Roman armies. They spent the winter of 73–72 BC training, arming and equipping their new recruits, and expanding their raiding territory to include the towns of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum.

In the spring of 72 BC, the rebels left their winter encampments and began to move northward. At the same time, the Roman Senate, alarmed by the defeat of the praetorian forces, dispatched a pair of consular legions under the command of Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. The two legions were initially successful—defeating a group of 30,000 rebels commanded by Crixus near Mount Garganus—but then were defeated by Spartacus.

Alarmed by the unstoppable rebellion, the Senate charged Marcus Licinius Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome and the only volunteer for the position, with ending the rebellion. Crassus was put in charge of eight legions, approximately 40,000 trained Roman soldiers, which he treated with harsh, even brutal, discipline, reviving the punishment of unit decimation. Crassus' legions were victorious in several engagements, forcing Spartacus farther south through Lucania as Crassus gained the upper hand. By the end of 71 BC, Spartacus was encamped in Rhegium, near the Strait of Messina.

Spartacus made a bargain with Cilician pirates to transport him and some 2,000 of his men to Sicily, where he intended to incite a slave revolt and gather reinforcements. However, he was betrayed by the pirates, who took payment and then abandoned the rebels. Spartacus' forces then retreated toward Rhegium. Crassus' legions followed and upon arrival built fortifications across the isthmus at Rhegium. The rebels were now under siege and cut off from their supplies.

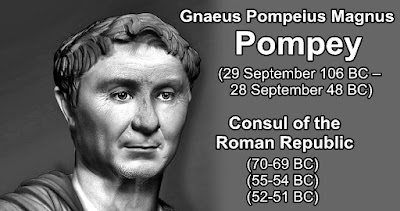

At this time, the legions of Pompey returned from Hispania and were ordered by the Senate to head south to aid Crassus. When the legions managed to catch a portion of the rebels separated from the main army, discipline among Spartacus' forces broke down as small groups were independently attacking the oncoming legions. Spartacus now turned his forces around and brought his entire strength to bear on the legions in a last stand. The final battle that saw the assumed defeat of Spartacus in 71 BC took place on the present territory of Senerchia on the right bank of the river Sale in the area that includes the border with Oliveto Citra up to those of Calabritto, near the village of Quaglietta, in High Sele Valley, which at that time was part of Lucania. Spartacus died during the battle, but his body was never found.

The rebellion of the Third Servile War was annihilated by Crassus. Although Pompey's forces did not directly engage Spartacus's forces at any time, his legions moving in from the north were able to capture some 5,000 rebels fleeing the battle. While most of the rebel slaves were killed on the battlefield, some 6,000 survivors were captured by the legions of Crassus. All 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way from Rome to Capua. Pompey and Crassus reaped political benefit for having put down the rebellion. Both Crassus and Pompey returned to Rome with their legions and refused to disband them, instead encamping outside Rome. Nonetheless, both men were elected consul for 70 BC, partly due to the implied threat of their armed legions encamped outside the city.

The revolt had shaken the Roman people, who out of sheer fear seem to have begun to treat their slaves less harshly than before. The wealthy owners of the latifundia began to reduce the number of agricultural slaves, opting to employ the large pool of formerly dispossessed freemen in sharecropping arrangements.

The legal status and rights of Roman slaves also began to change. During the time of Emperor Claudius, who reigned between 41–54 A.D., a constitution was enacted that made the killing of an old or infirm slave an act of murder, and decreed that if such slaves were abandoned by their owners, they became freedmen.

Under Antoninus Pius, who reigned between 138–161 A.D., laws further extended the rights of slaves, holding owners responsible for the killing of slaves, forcing the sale of slaves when it could be shown that they were being mistreated, and providing a (theoretically) neutral third party to which a slave could appeal. While these legal changes occurred much too late to be direct results of the Third Servile War, they represent the legal codification of changes in the Roman attitude toward slaves that evolved over decades.

It is difficult to determine the extent to which the events of this war contributed to changes in the use and legal rights of Roman slaves. The end of the Servile Wars seems to have coincided with the end of the period of the most prominent use of slaves in Rome and the beginning of a new perception of slaves within Roman society and law. The Third Servile War was the last of the Servile Wars, and Rome did not see another slave uprising of this magnitude again.