Sunday, April 9, 2023

The Inca Empire

The Inca Empire also known as the Incan Empire was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America, and possibly the largest empire

in the world in the early 16th century. Its political and administrative structure "was the most sophisticated found among native peoples" in the Americas.

Its official language was Quechua. Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the sun worship of Inti – their sun god – and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama. The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, to be the "son of the sun."

The term Inka means "ruler" or "lord" in Quechua and was used to refer to the ruling class or the ruling family. The Incas were a very small percentage of the total population of the empire, probably numbering only 15,000 to 40,000, but ruling a population of around 10 million persons. The Spanish adopted the term as an ethnic term referring to all subjects of the empire rather than simply the ruling class. As such the name Imperio inca referred to the nation that they encountered and subsequently conquered.

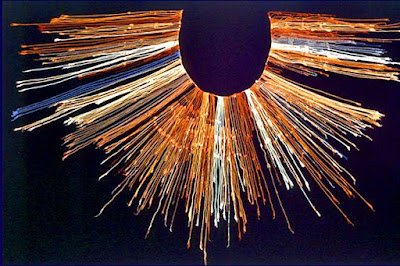

The Incas lacked the use of wheeled vehicles. They lacked animals to ride and draft animals that could pull wagons and plows. Incas lacked the knowledge of iron and steel. Above all, they lacked a system of writing. Despite these supposed handicaps, the Incas were still able to construct one of the greatest imperial states in human history". Notable features of the Inca Empire include its monumental architecture, especially stonework, extensive road network reaching all corners of the empire, finely-woven textiles, use of knotted strings, known as quipu, for record keeping and communication, agricultural innovations in a difficult environment, and the organization and management fostered or imposed on its people and their labor.

The Inca empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals and among individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. "Taxes" consisted of a labour obligation of a person to the Empire. The Inca rulers reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.

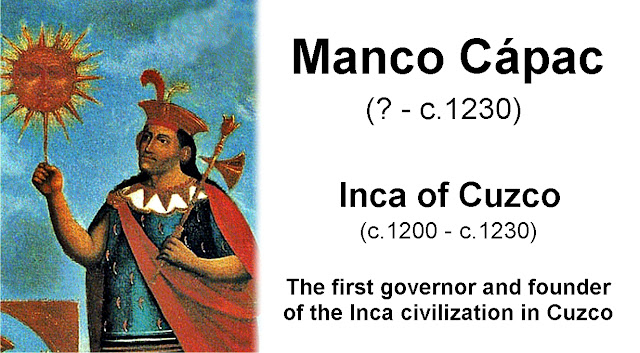

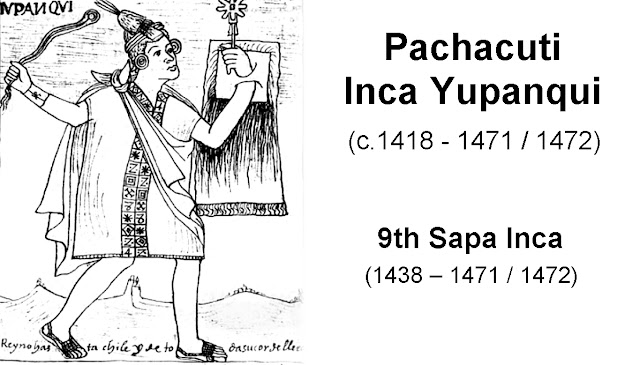

The Inca people were a pastoral tribe in the Cusco area around the 12th century. Under the leadership of Manco Cápac, the Inca formed the small city-state Kingdom of Cusco. In 1438, they began a far-reaching expansion under the command of Pachacuti-Cusi Yupanqui. During his reign, he and his son Tupac Yupanqui brought much of the Andes mountains, roughly modern Peru and Ecuador, under Inca control.

Pachacuti reorganized the kingdom of Cusco into the Tahuantinsuyu, which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with strong leaders. Pachacuti is thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or summer retreat, although it may have been an agricultural station. Pachacuti sent spies to regions he wanted in his

empire and they brought to him reports on political organization, military strength and wealth. He then sent messages to their leaders extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles and promising that

they would be materially richer as his subjects.

Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. Refusal to accept Inca rule resulted in military conquest. Following conquest the local rulers were executed. The ruler's children were brought to Cusco to learn about Inca administration systems, then return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate them into the Inca nobility and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Pachacuti's son Túpac Inca Yupanqui began conquests to the north in 1463 and continued them as Inca ruler after Pachacuti's death in

1471. Túpac Inca's most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the Peruvian coast. Túpac Inca's empire stretched north into modern-day Ecuador and Colombia.

Túpac Inca's son Huayna Cápac added a small portion of land to the north in modern-day Ecuador and in parts of Peru. At its height, the Inca Empire included Peru and Bolivia, most of what is now Ecuador and a large portion of what is today Chile, north of the Maule River. The advance south halted after the Battle of the Maule where they met determined resistance from the Mapuche. The empire's push into the Amazon Basin near the Chinchipe River was stopped by the Shuar in 1527. The empire extended into corners of Argentina and Colombia. However, most of the southern portion of the Inca empire, the portion denominated as Qullasuyu, was located in the Altiplano.

The Inca Empire was an amalgamation of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. The Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour.

Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro and his brothers explored south from what is today Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526. It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure, and after another expedition in 1529 Pizarro traveled to Spain and received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy.

When they returned to Peru in 1532, a war of brothers between the sons of Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa, and unrest among newly conquered territories weakened the empire. Perhaps more importantly, smallpox had spread from Central America. Pizarro did not have a formidable force. With just 168 men, one cannon,

and 27 horses, he often talked his way out of potential confrontations that could have easily wiped out his party. Along with their tactical and material superiority, the Spaniards acquired tens of thousands of native allies who sought to end the Inca control of their territories.

Their first engagement was the Battle of Puná, near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador, on the Pacific Coast; Pizarro then founded the

city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore the interior and returned with an invitation to meet the Inca, Atahualpa, who had defeated his brother in the civil war and was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops.

Pizarro and some of his men, most notably a friar named Vincente de Valverde, met with the Inca, who had brought only a small retinue. Through an interpreter Friar Vincente read the "Requerimiento" that demanded that he and his empire accept the rule of King Charles the first of Spain and convert to Christianity. Because of the language barrier and perhaps poor interpretation, Atahualpa became somewhat puzzled by the friar's description of Christian faith and was said to have not fully understood the

envoy's intentions. After Atahualpa attempted further enquiry into the doctrines of the Christian faith, the Spanish became frustrated and impatient. They attacked the Inca's retinue and captured Atahualpa as hostage.

Atahualpa offered the Spaniards enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in and twice that amount of silver. The Inca fulfilled this ransom, but Pizarro deceived them, refusing to release the Inca afterwards. During Atahualpa's imprisonment Huáscar was assassinated elsewhere. The Spaniards maintained that this was at Atahualpa's orders; this was used as one of the charges against Atahualpa when the Spaniards finally executed him, in August 1533.

The Spanish installed Atahualpa's brother Manco Inca Yupanqui in power; for some time Manco cooperated with the Spanish while they fought to put down resistance in the north. Meanwhile, an associate of Pizarro, Diego de Almagro, attempted to claim Cusco. Manco tried to use this intra-Spanish feud to his advantage,

recapturing Cusco in 1536, but the Spanish retook the city afterwards. Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba and established the small Neo-Inca State, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them. In 1572 the last Inca stronghold was conquered and the last ruler, Túpac Amaru, Manco's son, was captured and executed. This ended resistance to the Spanish conquest under the political authority of the Inca state.