Thursday, April 6, 2023

History of Siberia from stone age to Russian conquest

Siberia is characterised by a great deal of variety in climate, vegetation, and landscape. In the west, Siberia is bordered by the Ural Mountains. From there, the west Siberian lowlands extend to the east, all the way to the river Yenisei. Beyond this are the central Siberian highlands which are bordered on the east by the basin of the Lena River, beyond that are the northeast Siberian highlands. Siberia is bordered on the south by a rough chain of mountains and to the southwest by the hills of the Kazakh border.

The climate in Siberia is very variable. Yakutia, northeast of the Lena, is among the coldest places on Earth, but every year temperatures may vary for more than 50 °C, from as low as −50 °C in winter to over +20 °C in summer. The rainfall is very low. This is true of the southwest as well, where steppes, deserts and semi-deserts border on one another.

Agriculture is only possible in Siberia without artificial irrigation today between 50° and 60° north. The climatic situation is responsible for the different biomes of the region. In the northernmost section, there is tundra with minimal vegetation. The largest part of Siberia, aside from the mountainous regions, is taiga, northern coniferous forests. In the southwest this becomes forested steppe, and even further south it transitions to grass steppes and the central Asian desert.

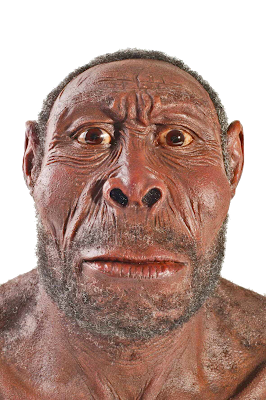

Finds from the Lower Paleolithic appear to be attested between east Kazakhstan and Altai. In the Upper Palaeolithic, by contrast, most remains are found in the Urals, where, among other things, rock carvings depicting mammoths are found, in Altai, on the upper Yenissei, west of Lake Baikal and around 25,000 on the shore of the Laptev Sea, north of the arctic circle. The remains of huts have been found in the settlement of Mal'ta near Irkutsk. Sculptures of animals and women, Venus figurines recall the European Upper Palaeolithic. The Siberian Palaeolithic continues well into the European Mesolithic. In the postglacial period, the taiga developed. Microliths, which are common elsewhere, have not been found.

In north Asia, the Neolithic, which was between 5500 and 3400 BC is mostly a chronological term, since there is no evidence for agriculture or even pastoralism in Siberia during the central European Neolithic. However, the neolithic cultures of North Asia are distinguished from the preceding Mesolithic cultures and far more visible as a result of the introduction of pottery.

Southwest Siberia reached a neolithic cultural level during the chalcolithic, which began here towards the end of the fourth millennium BC, which roughly coincided with the introduction of copper–working. In the northern and eastern regions, there is no detectable change.

In the second half of the third millennium BC, bronze working reached the cultures of western Siberia. Chalcolithic groups in the eastern Ural foothills developed the so-called Andronovo culture, which took various local forms. The settlements of Arkaim, Olgino und Sintashta are particularly notable as the earliest evidence for urbanisation in Siberia. In the valleys of the Ob and Irtysh the same ceramic cultures attested there during the neolithic continue. The changes in the Baikal region and Yakutia were very slight.

In the middle Bronze Age, between 1800 and 1500 BC, the west Siberian Andronovo culture expanded markedly to the east and even reached the Yenissei valley. In all the local forms of the Andronovo cultue, homogenous ceramics are found, which also extended to the cultures on the Ob. Here, however, unique neolithic ceramic traditions were maintained as well.

With the beginning of the late Bronze Age, between 1500 and 800 BC, crucial cultural developments took place in southern Siberia. The Andronovo culture dissolved and its southern successors produced an entirely new form of pottery, with bulbous ornamental elements. At the same time the southern cultures also developed new forms of bronze working, probably as a result of influence from the southeast. These changes were especially significant in the Baikal region. There, the chalcolithic material culture which had continued up to this time was replaced by a bronze-working pastoralist culture. There and in Yakutia, bronze was only used as a material for the first time at this point.

The cultural continuity on the Ob continued in the first millennium B.C., as the Iron Age began in Siberia. The local ceramic style continues there even in this period. A much larger break occurred in the central Asian steppe: the sedentary, predominantly pastoralist society of the late Bronze Age is replaced by the mobile horse nomads which would continue to dominate this region until modern times.

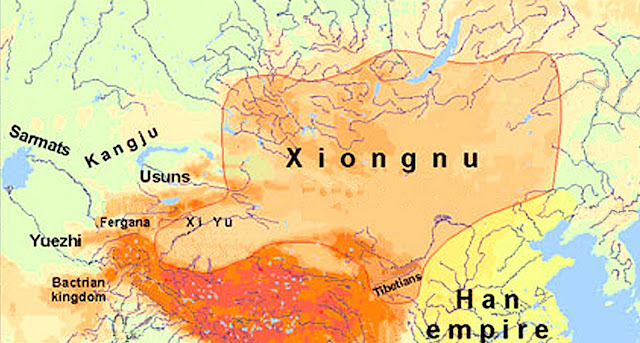

The mobility, which the new cultural form enabled, unleashed a powerful dynamic, since henceforth the people of Central Asia were able to move across the steppe in great numbers. The neighbouring sedentary cultures were not unaffected by this development. Ancient China was threatened by the Xiongnu and their neighbours, the ancient states of modern Iran were opposed by the Massagetae and Sakas, and the Roman empire eventually was confronted by the Huns. The social changes are clearly indicated in the archaeological finds. Settlements are no longer found, members of the new elite were buried in richly furnished kurgans and completely new forms of art developed.

In the damper steppes to the north, the sedentary pastoralist culture of the late Bronze Age developed under the influence of the material culture of the nomads. Proto-urban settlements like Tshitsha form the late Irmen culture in west Siberia and the settlements in the north of the Xiongnu cultural area.In many places the transition to later periods remains problematic due to the lack of archaeological evidence.

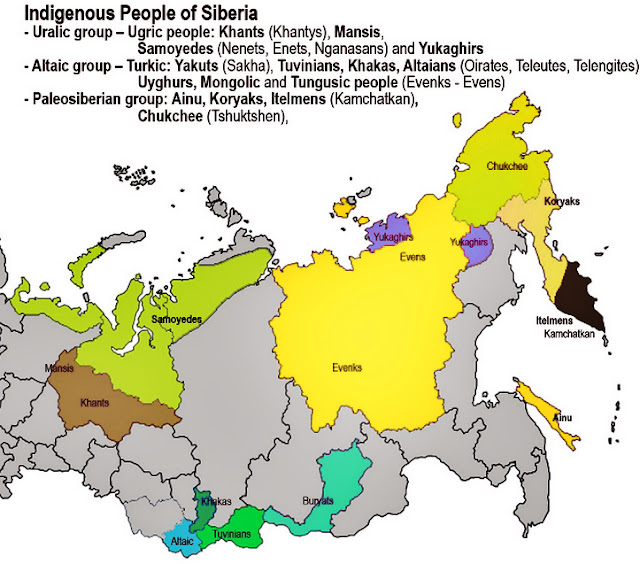

Nevertheless, some generalisations are possible. In the Central Asian steppes, Turkic groups become detectable sometime in the 5th century. Over the following centuries, they expand to the north and west until eventually they brought the whole of southern Siberia under their control. The area further north, where the speakers of Uralic and Paleosiberian languages were located is still poorly known.

The next clear break in the history of Siberia is the Russian expansion into the east which began in the 16th century and only concluded in the 19th century. This process marks the beginning of modernity in Siberia.