Saturday, April 8, 2023

The Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known as the Mexican War and in Mexico the American intervention in Mexico, was an armed conflict between the United States of America and the United Mexican States from 1846 to 1848.

After obtaining independence in 1821, from the Kingdom of Spain Mexico became a republic in 1824. It was characterized by considerable instability, leaving it ill-prepared for international conflict only two decades later when war broke out in 1846. Native American raids in Mexico's sparsely settled north in the decades preceding the war prompted the Mexican government to sponsor migration from the U.S.A. on its northeast border to the Mexican province of Texas to create a buffer.

However, the newly-named "Texians" revolted against the Mexican government of President - dictator Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana, who had usurped the Mexican constitution of 1824, in the subsequent 1836 Texas Revolution, creating a republic not recognized by Mexico, which still claimed it as part of its national territory. In 1845, the Texan Republic agreed to an offer of annexation by the U.S. Congress, and became the 28th state in the Union on December 29 that year.

Mexico severed relations with the United States in March 1845, shortly after the U.S. annexation of Texas. In September U.S. President James K. Polk sent John Slidell on a secret mission to Mexico City to negotiate the disputed Texas border, settle U.S. claims against Mexico, and purchase New Mexico and California for up to 30 million dollars.

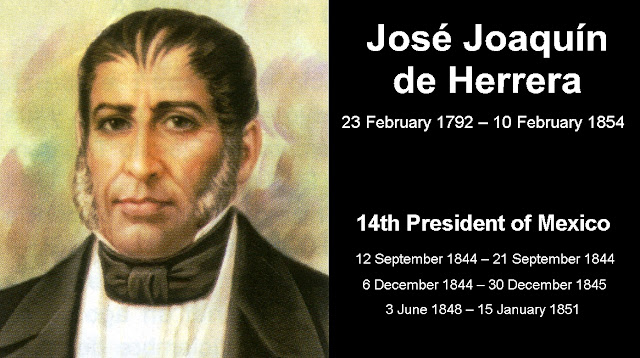

Mexican President José Joaquín Herrera, aware in advance of Slidell’s intention of dismembering the country, refused to receive him. When Polk learned of the snub, he ordered troops under

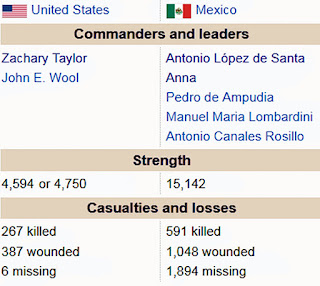

General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed area between the Nueces and the Rio Grande in January 1846.

Mexican forces attacked an American Army outpost in the occupied territory, killing 12 U.S. soldiers and capturing 52. These same Mexican troops later laid siege to an American fort along the Rio Grande. Polk cited this attack as a so-called invasion of U.S. territory, and requested that the Congress declare war.

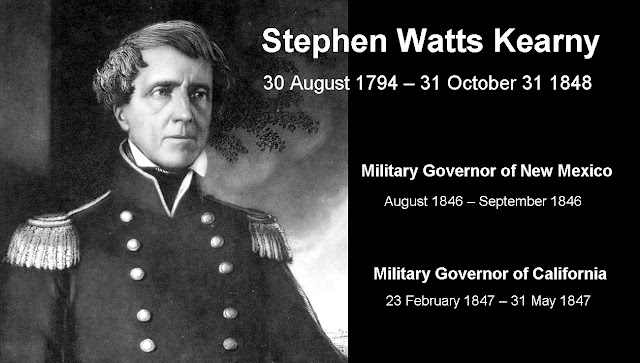

Following its original plan for the war, the United States sent its army from the Rio Grande, under Taylor, to invade the heart of Mexico while a second force, under Colonel Stephen Kearny, was to occupy New Mexico and California. At that time, only about 75,000 Mexican citizens lived north of the Rio Grande. As a result, U.S. forces led by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny and Commodore Robert F. Stockton were able to conquer those lands with minimal resistance. Taylor likewise had little trouble advancing, and he captured Monterrey in September.

Meanwhile, the Pacific Squadron of the United States Navy conducted a blockade, and took control of several garrisons on the Pacific Ocean western coast farther south in lower Baja California Territory.

With the losses adding up, Mexico turned to old standby General Antonio López de Santa Anna, the charismatic strongman who had been living in exile in Cuba. Santa Anna convinced Polk that, if allowed to return to Mexico, he would end the war on terms

favorable to the United States. But when he arrived, he immediately double-crossed Polk by taking control of the Mexican army and leading it into battle. At the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, Santa Anna suffered heavy casualties and was forced to withdraw. Despite the loss, he assumed the Mexican presidency the following month.

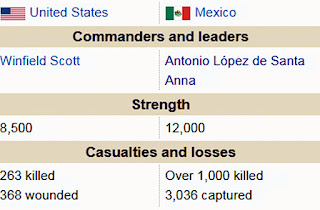

Meanwhile, U.S. troops led by General Winfield Scott performed the first major amphibious landing in U.S. history in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. A group of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers successfully offloaded supplies, weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing crafts. The Mexicans surrendered the city after 12 days under siege.

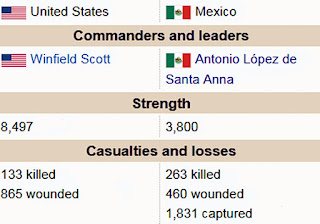

Scott then marched westward on April 2, 1847, toward Mexico City with 8,500 healthy troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon around the main road about 80 kilometers north-west of Veracruz, near the hamlet of Cerro Gordo. In the battle fought on April 18, the Mexican army was routed.

In May, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second largest city in Mexico. Because of the citizens' hostility to Santa Anna, the city capitulated without resistance on May 1.

The major objective of American operations in central Mexico had been the capture of Mexico City. After routing the Mexicans at the Battle of Churubusco, Scott's army was only 8 kilometers away from its objective of Mexico City. After Churubusco, fighting halted for an armistice and peace negotiations, which broke down on September 6, 1847. With the subsequent battles of Molino del Rey and of Chapultepec, and the storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Scott became military governor of occupied Mexico City.

Guerilla attacks against U.S. supply lines continued, but for all intents and purposes the war had ended. Santa Anna resigned, and the United States waited for a new government capable of negotiations to form.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo forced onto the remnant Mexican government, ended the war and specified its major consequence, the Mexican Cession of the northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México to the United States. The U.S. agreed to pay 15 million dollars compensation for the physical damage of the war. Mexico acknowledged the loss of their province, later Republic of Texas, and now State of Texas, and thereafter cited and acknowledged the Rio Grande as its future northern national border with the United States. Mexico had lost over one-third of its original territory from its 1821 independence.